Aaron Port stands under the thick canopy of leaves. Its dark eyes search for nests in the branches where green ants have settled. No sooner has he found her than it is already crawling on his hands and arms.

Aaron catches one of the stately ants and offers to try it: "Put it in your mouth and swallow it," he says. "They taste lemony." But the hoped-for effect is much more important than their taste: the green ants are said to drive away sore throats and cold symptoms.

On this tour, the man passes on the knowledge he has learned from generations of his ancestors. He belongs to the Kuku Yalanji, the Aboriginal people who live in tropical north Queensland - where the millennia-old rainforest meets the sea.

Aaron, who is called Kalkadudu in the language of his people, knows many plants that help in the treatment of various ailments.

"Sea Lettuce", sea lettuce, is the name of a meter-high bush with large light green leaves that grows directly on Wonga Beach north of Port Douglas. Its leaves cool sunburned skin.

The narrow, elongated leaf of a screw palm, rough on the inside, is tied with string around the head and goes about its normal business. "This rough texture acts like a massage, headaches go away with it."

The rainforest is full of plants that can help with ailments and diseases, says Aaron. Indigenous-led walkabout tours around Port Douglas offer a good insight into the healing powers of the bushes, trees and shrubs that grow so lush in the tropical climate.

Visitors can see the lush nature best by boarding the Cairns Skyrail, a gondola that soars above the rainforest canopy.

The forest is believed to have formed 135 million years ago and is believed to be the oldest tropical rainforest on the planet. For this reason, UNESCO declared it a world heritage site back in the 1980s.

At Red Peak, the first station of the gondola, a path leads through the dense forest. Everything seems to grow in all directions. In the struggle for sunlight, the plants are looking for their own way. “Everyone needs to see that they become growth winners,” says Skyrail's Marni Cadd.

The second stop offers a magnificent view of the Barron Falls. They are called "Din Din" by the local Djabuganydji and have been considered a holy place for thousands of years. During the rainy season between December and March, the Barron Falls swell into a lush waterfall. Visitors have the best view from the boardwalk that leads from the gondola to the gorge.

At the last cable car station in Kuranda, it is no longer the rainforest that plays the main role, but the eclectic place itself: a mixture of hippie oasis and Instagram spot.

Inland, 250 kilometers southwest of Cairns, there is a contrast to the rainforest. The Undara Volcanic National Park awaits here, or the "Undara Experience". At least that's how the landowners advertise it. And it is an experience, from the drive from Mareeba over many kilometers through nothing to the lava caves that formed here thousands of years ago.

The forest disappears, instead only a few eucalyptus trees, grasses, sparse bushes and huge termite mounds can be seen. The earth is becoming sandier and redder - just like in the hostile outback.

Sonya Fardell goes on exploration tours with visitors, because the sandy paths through the savannah are not open to the public. And you should also be familiar with the caves. "They were created when the last volcanoes erupted here."

That was 190,000 years ago. The lava flowed through the river beds, creating a tunnel system underneath through which the hot rock continued to flow – a total of 160 kilometers long. Only in Undara is access to some parts so well developed that you can walk a few hundred meters into different cave sections.

It's really exciting when night has fallen over the savannah. “Thousands of bats live in the caves and they are active in the dark,” says Sonya. They feed on the insects that swarm around here - and in turn are food for pythons and brown snakes that lurk at the cave entrances.

The day begins early in the morning with a bush brekkie, a rustic breakfast over an open fire, just like the first settlers with their cattle and covered wagons had every day in the mid-19th century. The coffee comes from a tin can, everyone is responsible for their own toast. The slices are browned in a metal rack over the fire. A real challenge at seven in the morning.

On the way from the holiday village to the breakfast area, there is a good chance of seeing one or the other kangaroo, wallaby or filander in the tall grass. The marsupials keep stretching their heads curiously. And the mums not only have a young animal in tow, but often also a "Joey", a baby, in their pouch.

"The marsupial mums have one young every year," says Margit Cianelli. She runs Lumholtz Lodge in Upper Barron, situated on the way from Undara through the Atherton Tablelands towards the coast.

The Swabian emigrated to Australia 50 years ago. In her lodge she welcomes nature lovers who want to be close to the animals. The rainforest begins right in front of their terrace.

It seems different than in the north around Port Douglas and Cairns. Huge trees, branches growing all over the place, tendrils threading between everything. tree kangaroos. And: lots of colorful birds that make themselves comfortable on the branches in front of the terrace and occasionally fly past the feeding station to nibble on a few seeds.

There's always something going on in Margit's kitchen, too, because the trained animal keeper regularly has animal guests there. In the corner next to the kitchen unit there are three warmly lined bags with white dots, in which several filanders and wallabies live.

On the door is another cloth bag with a hole that looks like grandmother's old staple bag. Animals grow there too, some of which are only a few months old. They are all orphans whom Margit has taken care of.

"The little kangaroos are only about the size of a grain of rice when they are born," she says.

After a gestation period of around 30 days, they must make it into the mother's pouch, where they can develop warmly and safely for months.

Margit feeds the orphans who are around the house and like to explore the area from the terrace. "As they get stronger and more self-sufficient, they unhook themselves over time and eventually stay in the wild," she says.

During their rainforest tours, the animals occasionally come across a distant relative that only exists here: the tree kangaroo, also known as the boongarry. The Norwegian naturalist Carl Sofus Lumholtz first described it about 100 years ago.

The Aborigines on the coast have known the Great Barrier Reef, which stretches 2,300 kilometers from Papua New Guinea to Queensland, for much longer: It consists of around 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands and, with its numerous habitats, is considered one of the most complex ecosystems the earth.

But the reef is going through a tough time. "Parts of the coral are dying or bleaching," says marine biologist Tess Concannon, who talks about life on the reef aboard a ship.

But despite the acute threat situation, there is a lot going on in the 27-degree warm water near Green Island off the coast of Cairns, even if it is raining cats and dogs and the wind is causing heavy waves.

All kinds of fish swim calmly from coral to coral, but the water is too turbulent to be able to watch them in peace. "Around ten percent of all fish known in the world live here in the Great Barrier Reef," says Tess.

You can snorkel or dive in the reef at carefully selected spots. Tess works at the only Aboriginal-led reef tour operator, Dreamtime Dive and Snorkel.

The team is mixed, Aboriginal and white Australians. The entire crew has exciting stories to tell. About the reef and the threats to the unique ecosystem. About traditional techniques of the indigenous people, such as making fire or painting bodies.

The reef is an integral part of the millennia-old history of the indigenous people who live here in the South Pacific. Brian Connolly, one of the Aborigines on the crew, pulls a dark something out of the water while snorkeling. It's a sea cucumber. The natives dived for them here and traded them with other tribes for food that the land gave them.

Because in Queensland there are dozens of Native American tribes. They all live according to their own traditions in and with the country.

Arrival: Currently only Singapore Airlines flies from Germany to Cairns with a stopover in Singapore. If you fly to Cairns via Sydney, you have the choice between different airlines, which often fly with a stop in Australia's largest city.

Entry: Germans need a passport that is still valid for at least six months and a tourist visa, which can be applied for online. Tourists arriving must be fully vaccinated against Covid-19, a current corona test is currently not required.

Climate and when to go: North Queensland is close to the equator and has tropical temperatures. The best, because driest, travel time is April to October - this is the winter half-year in Queensland.

Information: Tourism Tropical North Queensland, c/o Global Spot, Oberbrunner Str. 4, 81475 Munich (email: europe@ttnq.org.au; websites: www.tropicalnorthqueensland.org.au and www.queensland.com)

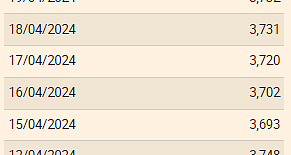

The Euribor today remains at 3.734%

The Euribor today remains at 3.734% Germany: the trial of an AfD leader, accused of chanting a Nazi slogan, resumes this Tuesday

Germany: the trial of an AfD leader, accused of chanting a Nazi slogan, resumes this Tuesday New York: at Columbia University, the anti-Semitic drift of pro-Palestinian demonstrations

New York: at Columbia University, the anti-Semitic drift of pro-Palestinian demonstrations What is Akila, the mission in which the Charles de Gaulle is participating under NATO command?

What is Akila, the mission in which the Charles de Gaulle is participating under NATO command? What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated)

What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated) Vaccination in France has progressed in 2023, rejoices Public Health France

Vaccination in France has progressed in 2023, rejoices Public Health France Food additives suspected of promoting cardiovascular diseases

Food additives suspected of promoting cardiovascular diseases “Even morphine doesn’t work”: Léane, 17, victim of the adverse effects of an antibiotic

“Even morphine doesn’t work”: Léane, 17, victim of the adverse effects of an antibiotic MEPs validate reform of EU budgetary rules

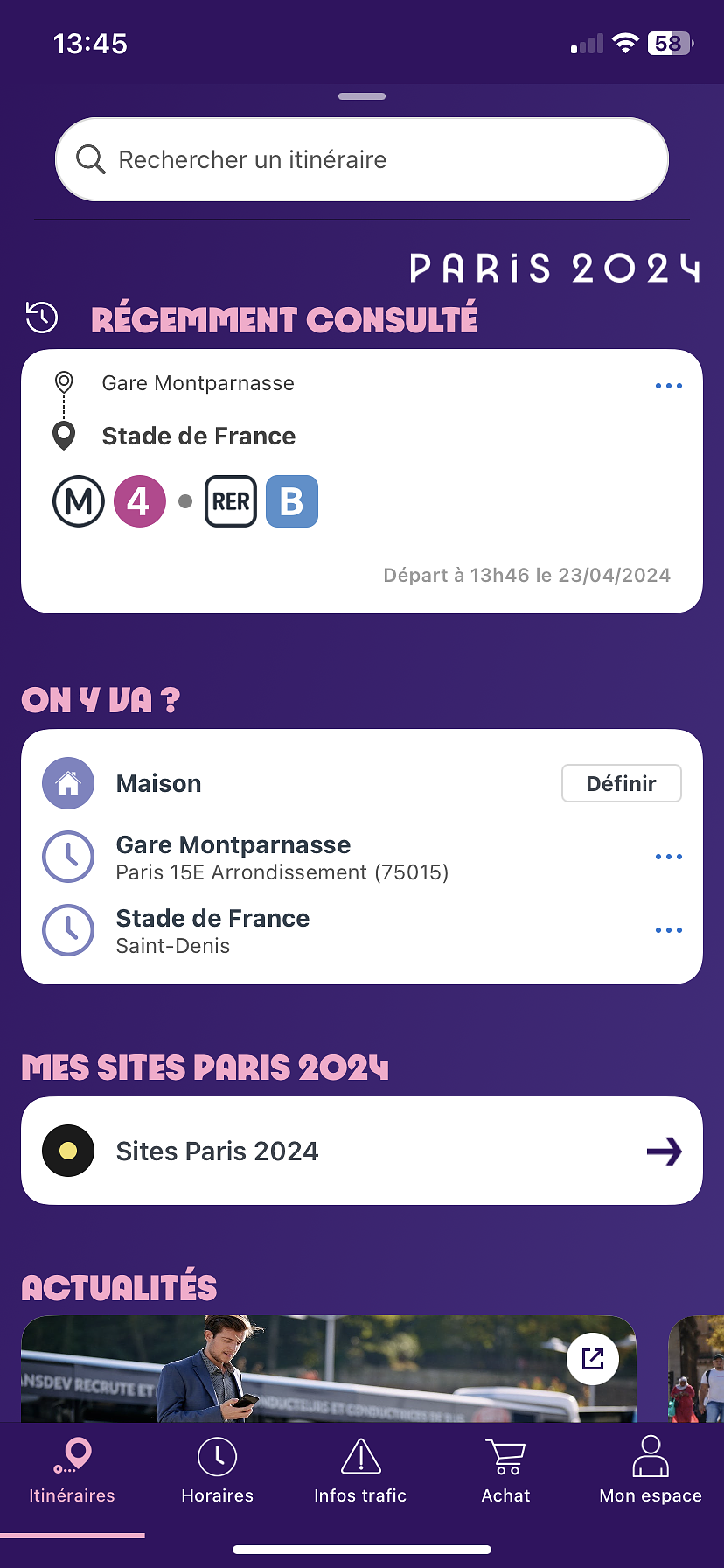

MEPs validate reform of EU budgetary rules “Public Transport Paris 2024”, the application for Olympic Games spectators, is available

“Public Transport Paris 2024”, the application for Olympic Games spectators, is available Spotify goes green in the first quarter and sees its number of paying subscribers increase

Spotify goes green in the first quarter and sees its number of paying subscribers increase Xavier Niel finalizes the sale of his shares in the Le Monde group to an independent fund

Xavier Niel finalizes the sale of his shares in the Le Monde group to an independent fund Owner of Blondie and Shakira catalogs in favor of $1.5 billion offer

Owner of Blondie and Shakira catalogs in favor of $1.5 billion offer Cher et Ozzy Osbourne rejoignent le Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

Cher et Ozzy Osbourne rejoignent le Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Three months before the Olympic Games, festivals and concert halls fear paying the price

Three months before the Olympic Games, festivals and concert halls fear paying the price With Brigitte Macron, Aya Nakamura sows new clues about her participation in the Olympics

With Brigitte Macron, Aya Nakamura sows new clues about her participation in the Olympics Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy

Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Serie A: Bologna surprises AS Rome in the race for the C1

Serie A: Bologna surprises AS Rome in the race for the C1 Serie A: Marcus Thuram king of Italy, end of the debate for the position of number 9 with the Blues?

Serie A: Marcus Thuram king of Italy, end of the debate for the position of number 9 with the Blues? Milan AC-Inter Milan: Thuram and Pavard impeccable, Hernandez helpless… The tops and flops of the derby

Milan AC-Inter Milan: Thuram and Pavard impeccable, Hernandez helpless… The tops and flops of the derby Ligue 2: Auxerre leader, Bordeaux in crisis, play-offs... 5 questions about an exciting end of the season

Ligue 2: Auxerre leader, Bordeaux in crisis, play-offs... 5 questions about an exciting end of the season