Picturesquely, the rocks of Chagyrskaya Cave tower over a river valley in the foothills of the Altai Mountains in Central Asia. Tens of thousands of years ago, groups of Neanderthals used this karst cave in southern Siberia, at least seasonally, as a hunting camp. The location of the cave - also spelled Tschagyrskaja - offers a good view over the valley through which herds of bison, horses and ibex once roamed. Hundreds of thousands of remains of bones and stone tools together with 80 Neanderthal fragments bear witness to the lively hunting activity at that time.

Today the cave provides a unique insight into the social structure of the Neanderthals who once lived here. Accordingly, the women usually left their groups and joined foreign clans. The findings may even apply in general to the closest relatives of Homo sapiens, who inhabited Eurasia between the Iberian Peninsula and the Altai Mountains from around 430,000 years ago until their extinction around 40,000 years ago.

In the journal "Nature", an international research team led by the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig uses genome analyzes of the inhabitants of the cave to gain insights into the way of life of these still largely mysterious cousins of Homo sapiens.

The authors of the study include Svante Pääbo; the director at the Leipzig Institute has just been awarded this year's Nobel Prize for Medicine and Physiology. He is considered the founder of paleogenetics - i.e. the study of prehistoric species based on their genetic material.

A few years ago, the Swede decoded the genome of the Neanderthals. And a little later, from finds in the Denisova Cave, also in the Altai Mountains, he identified a new group of people: the Denisovans were closely related to the Neanderthals, but lived further east, in Central and East Asia. Thanks to Pääbo's research, we know that both human species interbred with each other and with Homo sapiens tens of thousands of years ago.

The group led by the Leipzig researchers Laurits Skov and Benjamin Peter reconstructed the genomes of 13 Neanderthals from bones and teeth: 11 of these men, women and children lived in the Chagyrskaya Cave roughly 54,000 years ago, the other two a little earlier in the nearby Okladnikov Cave. Cave. For comparison: only 18 comparable genome data from Neanderthals from 14 different sites had previously been published.

While previous paleogenetic Neanderthal analyzes provided information about rough degrees of relationship and migration movements, the current work goes far beyond that. Lara Cassidy of Trinity College Dublin writes of a "milestone" in a Nature commentary: "What makes this study particularly remarkable is that the sequenced individuals are not widely scattered across the vast expanse of Neanderthal existence, but are contiguous at a point in time and space, offering the first snapshot of a kinship.”

Among the 11 individuals whose remains came from Chagyrskaya, the team identified a father and his teenage daughter. The scientists also found an eight to twelve-year-old boy and an adult woman who were second-degree relatives: According to this, the woman could have been the boy's cousin, aunt or grandmother.

But that's not all: further analyzes indicate that the individuals examined may have inhabited the cave at the same time. "Taken together, the data support the suspicion that all eleven Chagyrskaya Neanderthals were part of the same community," the team writes.

Because the individuals examined have a very low genetic diversity, the researchers assume a small group size. Accordingly, the community consisted of about 20 individuals. French researchers came up with a similar size of a Neanderthal group in 2019 using a different approach: they had examined dozens of footprints in Le Rozel in Normandy and assumed there were 10 to 13 individuals.

Small groups are not uncommon in Homo sapiens for traditional hunter-gatherers either. Group size is a balancing act and depends on the environment, says Jean-Jacques Hublin, director emeritus at the Leipzig Institute and not involved in the work. Accordingly, groups need a certain minimum size so that they can survive safely and establish a new generation, on the other hand they must not have more members than can be fed.

In any case, such groups did not live in complete isolation, but probably in a kind of network with other communities in the area. Another result of the study shows how this could be organised. Because the team examined both the genetic diversity on the Y chromosome, which is inherited from father to son, and the diversity of the mitochondrial DNA, which the mother passes on to the children.

Accordingly, the mitochondrial genetic diversity was higher by a factor of about 10. Therefore, the team suspects that at least 60 percent of the women left their own community and joined other tribes. "The men were more closely related to each other, the women came from outside," explains Hublin.

Indications of such a way of life - known in technical jargon as patrilocal - had already been described by researchers in 2010 after analyzing finds from the El Sidrón cave in the northern Spanish region of Asturias. They examined the Neanderthal genomes of three women and three men. They analyzed the genetic material in the mitochondria - the power plants of the cells - which is only inherited through the maternal line. The investigation revealed that the three adult males descended from the same ancestral line, but each of the three females from a different line.

At the time, the researchers interpreted this as evidence of a patrilocal way of life - although the interpretation was controversial. The current study supports the interpretation at that time, writes "Nature" commentator Cassidy: "Skov et al. provide the most compelling evidence of such behavior to date.”

The result also fits the social structure of early Homo sapiens communities, says Hublin. "There are exceptions, but in most traditional human societies, women are more mobile than men." This may have served to tie multiple groups together. And: Inbreeding is thus limited.

Hublin emphasizes that patrilocality is not only found in humans, but also in our closest animal relatives, the chimpanzees. "There, too, the males remain in the group in which they were born," says Hublin.

The researchers emphasize in "Nature" that it is unclear whether their findings only apply to the inhabitants of the remote Altai Mountains or to Neanderthals in general. "Our study paints a very concrete picture of what a Neanderthal community might have looked like," says co-author Peter. "That makes the Neanderthals seem much more human to me."

How similar Homo sapiens and Homo neanderthalensis really were remains to be seen. "Neanderthals were complex beings, but they were probably different from us in many ways," says anthropologist Hublin. "That's what makes them all the more fascinating."

His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction

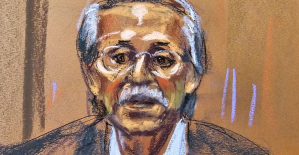

His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial?

Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial? What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain?

What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain? The shadow of Chinese espionage hangs over Westminster

The shadow of Chinese espionage hangs over Westminster Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50

Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50 H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States

H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated)

What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated) Vaccination in France has progressed in 2023, rejoices Public Health France

Vaccination in France has progressed in 2023, rejoices Public Health France The right deplores a “dismal agreement” on the end of careers at the SNCF

The right deplores a “dismal agreement” on the end of careers at the SNCF The United States pushes TikTok towards the exit

The United States pushes TikTok towards the exit Air traffic controllers strike: 75% of flights canceled at Orly on Thursday, 65% at Roissy and Marseille

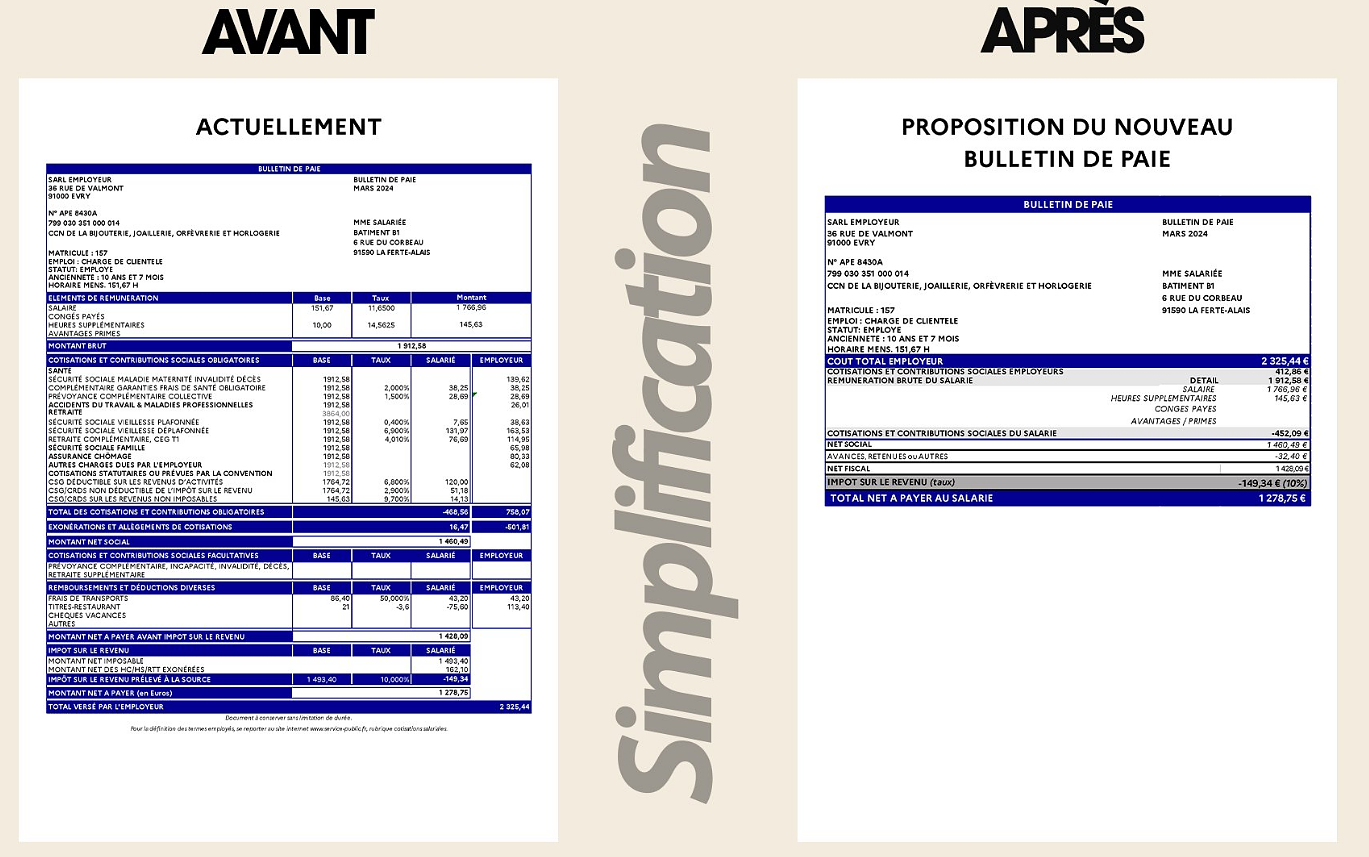

Air traffic controllers strike: 75% of flights canceled at Orly on Thursday, 65% at Roissy and Marseille This is what your pay slip could look like tomorrow according to Bruno Le Maire

This is what your pay slip could look like tomorrow according to Bruno Le Maire Sky Dome 2123, Challengers, Back to Black... Films to watch or avoid this week

Sky Dome 2123, Challengers, Back to Black... Films to watch or avoid this week The standoff between the organizers of Vieilles Charrues and the elected officials of Carhaix threatens the festival

The standoff between the organizers of Vieilles Charrues and the elected officials of Carhaix threatens the festival Strasbourg inaugurates a year of celebrations and debates as World Book Capital

Strasbourg inaugurates a year of celebrations and debates as World Book Capital Kendji Girac is “out of the woods” after his gunshot wound to the chest

Kendji Girac is “out of the woods” after his gunshot wound to the chest Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy

Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar NBA: the Wolves escape against the Suns, Indiana unfolds and the Clippers defeated

NBA: the Wolves escape against the Suns, Indiana unfolds and the Clippers defeated Real Madrid: what position will Mbappé play? The answer is known

Real Madrid: what position will Mbappé play? The answer is known Cycling: Quintana will appear at the Giro

Cycling: Quintana will appear at the Giro Premier League: “The team has given up”, notes Mauricio Pochettino after Arsenal’s card

Premier League: “The team has given up”, notes Mauricio Pochettino after Arsenal’s card