The prime minister no longer wanted to be head of government. The parties in Italy were so divided in the late summer of 1922 that they were unable to agree on a new cabinet. Only at the personal request of the head of state did the previous Prime Minister Luigi Facta agree to form another team of ministers. Of course, an effective government could not emerge in this way.

For Benito Mussolini, this was the opportunity of a lifetime. The 'Duce' ('leader') of the Partito Nazionale Fascista (PNF) realized that now all that was needed was a nudge to bring down the weak Italian state and seize power for himself. The eloquent former socialist had his supporters mobilized everywhere in Italy, organizing demonstrations, meetings and parades.

A hundred years later, the situation in Italy is astonishingly similar to the situation in the late summer of 1922: once again, the hitherto dominant party alliances, the centre-right camp, the centre-left camp and the populist, anti-establishment Five Stars movement, are hopelessly at odds. Once again, the previous Prime Minister, Mario Draghi, resigned and was only in office as an executive.

And again, a right-wing party seized the opportunity: the parliamentary elections on September 25, 2022 were clearly won by the Fratelli d'Italia (Brothers of Italy), which go back to the neo-fascists (Movimento Sociale Italiano) founded in 1946.

Unlike 2022, Mussolini and his party could not build on a fairly clear electoral victory in 1922. Instead, the “Duce” relied on personnel policy. In order to survive the war of nerves with the Facta government, to which the Italian army was still loyal, Mussolini appointed Emilio De Bono, a respected World War I general, to the leadership of his fascist militias, the “Black Shirts”.

Thus there was a reference person for each of the main groups that fascism had to win over: for the active soldiers General De Bono, for the monarchists the lawyer Cesare Maria De Vecchi, for the often young veterans of the fighting from 1915 to 1918 the officer with front-line experience Italo Balbo and for the workers the ex-unionist Michele Bianchi.

This increased concern that the fascists were planning a coup d'etat. Bianchi could not dispel this suspicion, although he announced on October 6: “It is true, very true, that we have spoken and are still speaking of a 'March on Rome', but it is a march that – should be even the most layman can understand it – quite spiritually, I would like to say: legal is.” At least Luigi Facta obviously didn’t believe that, because he had the forts around Rome alerted. The prime minister assured concerned MPs: "I have ordered that the guns be greased."

The decision was made on October 16, 1922. On this day, Mussolini called a PNF party conference in Naples at short notice for the coming week. Following this public show, on October 27th, all “blackshirts” would mobilize, occupy “public buildings in the most important cities” in their home regions, i.e. town halls, police stations, train stations and post offices, then come to assembly points around Rome. With this threatening backdrop, an "ultimatum to the Facta government for the general cession of state power" was to be issued, followed by the "invasion of Rome".

Between 15,000 and 30,000 men attended the party congress in Naples, a traditionally left-wing region. Mussolini thundered in his speech: "I swear that either the government of this country will be passed peacefully to the fascists or we will take it by force!" The audience chanted: "To Rome!" Mussolini himself, however, first traveled home to Milan and left the rest to the four men at the head of the militia. For him, the actual "march" on the capital played a minor role. It was all about the threat potential.

On October 26, Facta and his interior minister warned all prefectures about fascist uprisings. Despite this, the authorities could not prevent "black shirts" from occupying key positions in various cities. First up was Pisa, then Siena, later on the same day Cremona and Perugia. As soon as the fascists had control of the situation in a city, they confiscated trucks and cars in order to send as many militiamen as possible to Rome.

Panic gripped the cabinet: Prime Minister Luigi Facta resigned in the middle of the open attack on the state - he wanted to make room for a "strong government", an American journalist learned. A little later, the only executive cabinet decided to ask the king to impose a state of siege, i.e. martial law. Furthermore, the balance of power spoke in favor of the state: On October 27, there were at most 5,000 “black shirts” at the collection points around Rome, and about twice as many were on the way. The army had significantly more soldiers at its disposal in the garrisons in and around the capital.

But the unsettled state administration was unable to counteract the dynamics of the fascists: On the night of October 27th, “blackshirts” occupied dozens of other cities from Trieste and Venice in the north-east to Foggia in the south-east, from Aquila in Abruzzo to Alessandria in the northwest prefectures and post offices.

On the morning of October 28, fascists controlled communications in most towns in northern and central Italy; in the south they were far less strong. In Rome the situation was calm. Since midnight, soldiers loyal to the government have been securing strategic points in the city, including the royal palace.

At six o'clock in the morning the caretaker government met and drafted the state of siege law, which was already in effect. Luigi Facta took the design to Vittorio Emanuele III, expecting the monarch to endorse it. But the king, disgusted by the vacillating policies of the prime minister and his partners, declined. He was convinced that the only way to prevent the fascists from taking over the government was to wage a civil war. Around noon, martial law, which had not even been formally imposed, was lifted.

On the afternoon of October 28, when the army and police had largely withdrawn to their barracks, "blackshirts" cracked down on independent and left-wing newspapers in many cities. Editorial offices and printers were occupied, and printing presses were damaged or even destroyed. The fascist revolution was on the rise.

The following morning the King sent a telegram to Benito Mussolini in Milan and offered him the post of Prime Minister. The Duce accepted and took the night train to Rome. The news gave the fascists the upper hand: on the morning of October 30, thousands of Mussolini supporters organized spontaneous joyful processions in the capital.

At the assembly points around Rome, "blackshirts" were still waiting for the order to march, now 30,000 to 40,000 men. Most were dissatisfied: It was raining cats and dogs, there were hardly any tents, let alone prepared latrines, and there was even a lack of food. But on October 30, the state put things right – the army took care of the soaked fascists, and so they set off after all. On October 31, the “March on Rome”, which was no longer necessary, actually took place.

In some working-class areas of the capital, barricade fights broke out between “black shirts” and communists, in which around 20 people died and around a hundred were injured. Then Mussolini had won. His plan to threaten massive violence up to and including open civil war and to offer himself as a guarantor of public order in this situation, which was at least largely caused by his supporters, had worked perfectly.

The events in Italy were closely observed worldwide. After Mussolini's victory, the internationally well-connected ex-diplomat Harry Graf Kessler wrote in his diary: "The fascists seized power in Italy with a coup d'etat." historical event that can have unforeseeable consequences not only for Italy but for the whole of Europe.”

A little later, a young man named Hermann Esser appeared in Munich, who adorned himself with the title "Propaganda leader". He shouted at the supporters of the NSDAP splinter party gathered in the Krone circus: “In Italy, a handful of nationally minded men have succeeded in creating order. We too will have a Mussolini if order cannot be achieved otherwise. It is the leader of the National Socialists, Adolf Hitler.” And Esser added: “Only the national dictatorship can create order, parliamentarism is a swindle.”

This is a feeling that was expressed in a very similar way in the 2022 Italian election campaign. Truly a parallel to fear.

You can also find "World History" on Facebook. We are happy about a like.

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction

His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial?

Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial? What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain?

What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain? Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50

Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50 H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States

H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated)

What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated) Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation

Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application

Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application “I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing

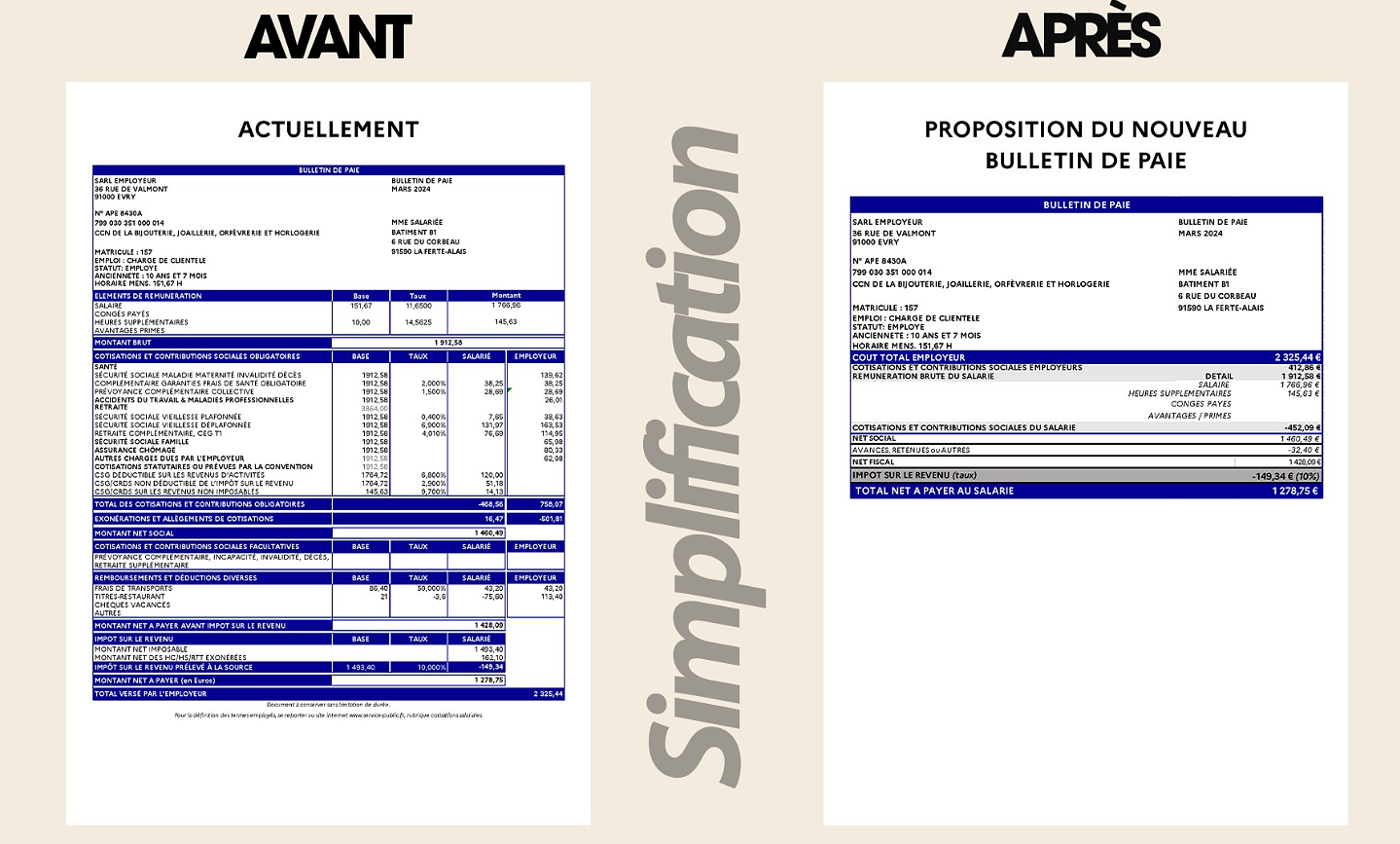

“I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing “I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy

“I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy 25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits

25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan

At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga

Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker

Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League

Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops

OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet

Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid

Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid