I never really feel comfortable in Bolivia. Even the start was bumpy when I had to wait hours for clearance at the Argentine-Bolivian border. Above all, however, traveling by bus is, to put it diplomatically, adventurous. You never know what to expect.

On the way to Sucre, my bus stops about 15 kilometers before the city limits, apparently for no reason. Only when asked does the bus driver explain that Sucre introduced a car-free day for the first time on this Sunday of all days. So we stand around in the middle of nowhere for around two hours until around 6 p.m. cars are allowed back into the city.

Expectations for Sucre are high, as many other travelers have raved to me about how great the city is. And yes, the city center is really pretty with its mostly white colonial buildings. The highlight is the central square (Plaza 25 de Mayo de Sucre), where people meet to idle.

After seeing my fill of the old town, I continue to La Paz with a stopover in Cochabamba. On the way from Sucre to Cochabamba I experience what is probably the most winding road in the world. The driver races around the never-ending bends in the fully packed minibus so quickly that I – one of the few times on my trip around the world – have to take an anti-nausea pill. Hours later, my head still feels like I'm drunk.

The next day it's off to La Paz in the big coach. I'm happy to take a seat in the first row on the top floor, directly above the driver's cab. Premium view! But I was happy too soon: the sun beats down on me mercilessly for hours because I'm sitting unprotected in front of the panoramic glass pane. My sunglasses offer little protection. And as is so often the case, the air conditioning does not work on this bus either. Even I lose interest in the magnificent mountain views.

What's more, I'm sitting in a lame carriage. Stupidly, this "carriage" has to cross huge mountain ranges. But that doesn't stop the bus driver from daring the most impossible overtaking manoeuvres.

In any case, I break out in a sweat from my box seat in the first row, as I have to watch the bus driver slowly trying to overtake a long articulated lorry before an uphill bend. I don't think it's a good omen that many oncoming drivers cross themselves in front of us. But the gestures seem to help: Miraculously, we arrive safely in La Paz.

Traffic in Bolivia is generally annoying. This is mainly due to the unbearable air pollution caused by many scrap cars. When an old bus drives past you and leaves a dark cloud of exhaust gases in your wake, you are happy to be wearing the respirator mask that is mandatory because of Covid on the street.

But breathing is otherwise difficult in Bolivia. Although I spend several weeks mostly at an altitude of over 3500 meters, my body does not really acclimate. I never sleep through the night, even on the last day in Bolivia I was plagued by gasping and exhaustion.

Each of the countless climbs takes my breath away. It's hard to feel comfortable in a country where you can't breathe really well. But I also know that other travelers cope better with the mountain air.

Despite poor breathing, I can get excited about La Paz. Although many travelers describe the city as a juggernaut, I don't feel that way. Probably because I've already experienced places like Delhi and Mumbai in India that offer a completely different dimension of chaos.

Instead, I'm fascinated by how a city of millions can be built on mountain slopes that are difficult to access. So in La Paz it's really only uphill or downhill. Luckily, a state-of-the-art cable car system was built a few years ago. All ten lines are connected with each other, so you can circumnavigate almost the entire city with a combination ticket. It feels like the biggest roller coaster in the world and the views along the way are nothing short of spectacular.

If you want to move yourself, I recommend the descent on "the most dangerous road in the world". There are tours available all over the city. It goes in small groups to an altitude of about 4600 meters.

There you get a mountain bike with protective clothing and a briefing. And off we go. 3000 meters downhill! First on asphalt, later on a lot of gravel. Despite the striking title, the route offers enough safety distance for bicycles to the unsecured mountain slopes and gorges.

After this fun, I continue to Lake Titicaca at the end of my Bolivia trip - unfortunately back on the bus.

Read more parts of the world tour series “One Way Ticket” here.

This article was first published in June 2022.

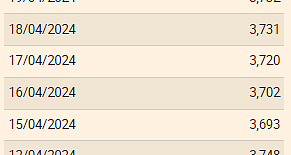

The Euribor today remains at 3.734%

The Euribor today remains at 3.734% Germany: the trial of an AfD leader, accused of chanting a Nazi slogan, resumes this Tuesday

Germany: the trial of an AfD leader, accused of chanting a Nazi slogan, resumes this Tuesday New York: at Columbia University, the anti-Semitic drift of pro-Palestinian demonstrations

New York: at Columbia University, the anti-Semitic drift of pro-Palestinian demonstrations What is Akila, the mission in which the Charles de Gaulle is participating under NATO command?

What is Akila, the mission in which the Charles de Gaulle is participating under NATO command? What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated)

What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated) Vaccination in France has progressed in 2023, rejoices Public Health France

Vaccination in France has progressed in 2023, rejoices Public Health France Food additives suspected of promoting cardiovascular diseases

Food additives suspected of promoting cardiovascular diseases “Even morphine doesn’t work”: Léane, 17, victim of the adverse effects of an antibiotic

“Even morphine doesn’t work”: Léane, 17, victim of the adverse effects of an antibiotic MEPs validate reform of EU budgetary rules

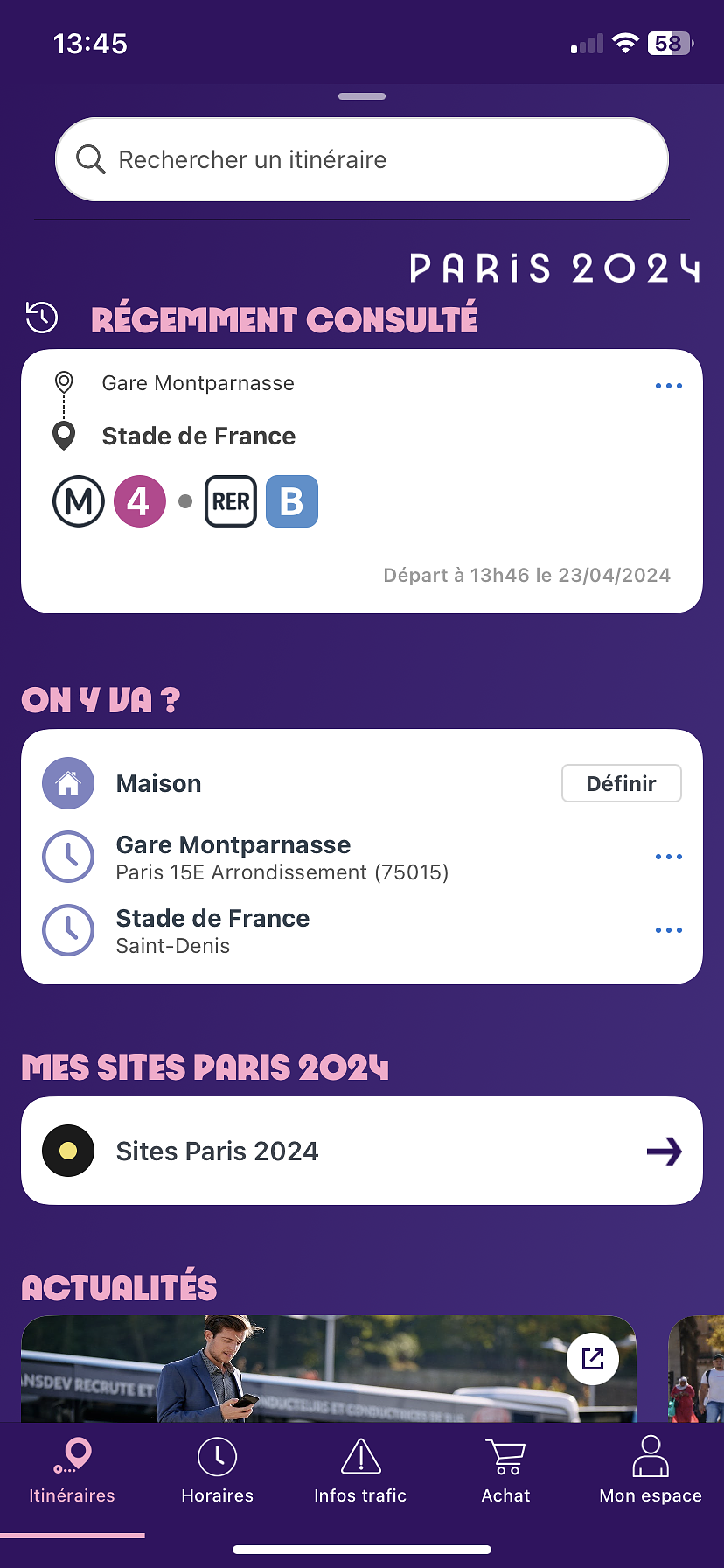

MEPs validate reform of EU budgetary rules “Public Transport Paris 2024”, the application for Olympic Games spectators, is available

“Public Transport Paris 2024”, the application for Olympic Games spectators, is available Spotify goes green in the first quarter and sees its number of paying subscribers increase

Spotify goes green in the first quarter and sees its number of paying subscribers increase Xavier Niel finalizes the sale of his shares in the Le Monde group to an independent fund

Xavier Niel finalizes the sale of his shares in the Le Monde group to an independent fund Owner of Blondie and Shakira catalogs in favor of $1.5 billion offer

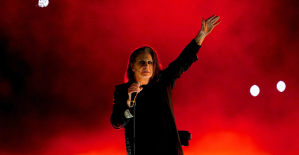

Owner of Blondie and Shakira catalogs in favor of $1.5 billion offer Cher et Ozzy Osbourne rejoignent le Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

Cher et Ozzy Osbourne rejoignent le Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Three months before the Olympic Games, festivals and concert halls fear paying the price

Three months before the Olympic Games, festivals and concert halls fear paying the price With Brigitte Macron, Aya Nakamura sows new clues about her participation in the Olympics

With Brigitte Macron, Aya Nakamura sows new clues about her participation in the Olympics Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy

Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Serie A: Bologna surprises AS Rome in the race for the C1

Serie A: Bologna surprises AS Rome in the race for the C1 Serie A: Marcus Thuram king of Italy, end of the debate for the position of number 9 with the Blues?

Serie A: Marcus Thuram king of Italy, end of the debate for the position of number 9 with the Blues? Milan AC-Inter Milan: Thuram and Pavard impeccable, Hernandez helpless… The tops and flops of the derby

Milan AC-Inter Milan: Thuram and Pavard impeccable, Hernandez helpless… The tops and flops of the derby Ligue 2: Auxerre leader, Bordeaux in crisis, play-offs... 5 questions about an exciting end of the season

Ligue 2: Auxerre leader, Bordeaux in crisis, play-offs... 5 questions about an exciting end of the season