Anyone who holds on to a promise that can no longer be kept for too long loses. After all, pragmatism and well-considered, timely adjustments to developments are always better than inaction. This is always the case in politics, but above all in monetary policy, which is particularly dependent on the psychology of the markets and is therefore highly sensitive.

In 1944, the western states, led by the USA, had devised a new currency system for the world for the time after the foreseeable victory in the Second World War, which included the stability of the traditional gold standard (in which paper money was always exchanged for gold by the issuing central bank on request). the advantages of limited flexible exchange rates - which gave governments and central banks the opportunity to stimulate the development of the domestic economy through moderate appreciation or devaluation of their own currency.

The result came to be known as the Bretton Woods system, and stipulated that the Federal Reserve would exchange dollars for gold (at the stipulated short of $35 an ounce) while simultaneously having an obligation on the central banks to quote exchange rates on the open market to stabilize against the dollar as the key currency by buying or selling foreign exchange. The newly created International Monetary Fund as a supranational institution was supposed to control and support the system.

This resulted in a currency structure that was largely stable for a quarter of a century: the pound sterling, for example, fluctuated between 1953 and 1967 only between 2.77 and 2.82 dollars, i.e. by 2.5 percent, the Swiss franc between 0.22 and 0 .24 dollars. Bretton Woods worked because currencies were repeatedly revalued or devalued in consultation with the central banks. The West German mark, for example, was revalued in 1961 from 4.20 DM per dollar to four DM per dollar, and in 1969 again to 3.66 DM per dollar - the less DM had to be paid for a dollar, the higher its value as a currency.

But by 1970 the Bretton Woods system was no longer tenable. This had to do with an insoluble conflict of goals, the “trilemma of the exchange rate regime”. If the goals of politics should be exchange rates that are as stable as possible and monetary policy autonomy for the individual central banks (or governments) and capital should also be able to move freely, then in principle a maximum of two of these goals can be achieved at the same time, but never all three.

Because the federal government of Chancellor Willy Brandt had largely freed the exchange rate from the mark to the dollar in May 1971 and the US currency then plummeted by almost ten percent against West German money, there was an urgent need for action in the summer. All experts eagerly awaited what would happen - and when.

On August 15, 1971, the time had come: US President Richard Nixon overturned the dollar's gold link, effectively freeing the gold exchange rate. The US currency has been under pressure for years because the government in Washington spent much more (e.g. for the Vietnam War and the space program) than was available in terms of economic power. All of a sudden, US tourists abroad found themselves without money because their dollar bills were no longer accepted by banks. Worse still, international trade relations threatened to collapse.

"Every large industrialized country today is constrained in its internal economic policy because it has to take foreign trade relationships into account with fixed exchange rates," WELT explained the basic relationships: "Only the USA was able to turn to domestic issues undisturbed, without thinking about the international consequences to have to."

But in the meantime the economic pressure had become too great - the British pound had already appreciated in 1967 from $2.78 to $2.38 and even the French franc from $0.20 to $0.18. The US government had to react.

There were basically two options: Either, as the US economist Paul A. Samuelson had suggested, the rate of $35 per troy ounce of gold had to be increased. Saluelson's word carried weight, having just been awarded the 1970 Nobel Prize in Economics.

On the one hand, however, this would have benefited gold speculators and the Soviet Union, which is strong in gold as a raw material. On the other hand, it would have been unclear whether such a measure would have really improved the competitiveness of the USA to any significant degree. The next adjustment would probably have been necessary soon – entering a permanent devaluation crisis.

So, against Samuelson's advice, the Washington government opted for the second option: a 10 percent levy was imposed on all imports into the US (which made imports more expensive for the domestic market, making US products more attractive to the domestic market) and at the same time the guaranteed exchange of the de facto devalued dollar into gold was suspended.

The reaction was immediate: Most economically strong countries immediately closed foreign exchange trading because they feared being swamped by “freely roaming dollars” (WORLD). Because, of course, every dollar owner tried to exchange this money for currencies that were suspected of being revalued. The term “Nixon money crunch” became commonplace for the phenomenon.

Nevertheless, the dollar fell – against the Japanese yen and the Swiss franc, for example, by almost ten percent each. The Federal Republic and the Netherlands were protected against floods of dollars by the fact that their currencies had already been revalued via freely fluctuating exchange rates.

Bretton Woods basically failed, but as is well known, those who are declared dead sometimes live longer. The world currency system, which had been poorly repaired in the late summer of 1971, dragged on for another year and a half. It was not until February 1973 that the Western European countries and Japan officially broke their ties to the dollar as their reserve currency.

Gold, always coveted for more psychological reasons as an emergency reserve in times of crisis, rose to $615 an ounce by 1975, then plummeted back to $271 in 2001. It has since rallied to $1920 on September 1, 2020, at However, there are always possible price breaks of five to ten, sometimes (like 2014) by almost 25 percent.

You can also find "World History" on Facebook. We are happy about a like.

Sydney: Assyrian bishop stabbed, conservative TikToker outspoken on Islam

Sydney: Assyrian bishop stabbed, conservative TikToker outspoken on Islam Torrential rains in Dubai: “The event is so intense that we cannot find analogues in our databases”

Torrential rains in Dubai: “The event is so intense that we cannot find analogues in our databases” Rishi Sunak wants a tobacco-free UK

Rishi Sunak wants a tobacco-free UK In Africa, the number of millionaires will boom over the next ten years

In Africa, the number of millionaires will boom over the next ten years WHO concerned about spread of H5N1 avian flu to new species, including humans

WHO concerned about spread of H5N1 avian flu to new species, including humans New generation mosquito nets prove much more effective against malaria

New generation mosquito nets prove much more effective against malaria Covid-19: everything you need to know about the new vaccination campaign which is starting

Covid-19: everything you need to know about the new vaccination campaign which is starting The best laptops of the moment boast artificial intelligence

The best laptops of the moment boast artificial intelligence Bitcoin halving: what will the planned reduction in emissions from the queen of cryptos change?

Bitcoin halving: what will the planned reduction in emissions from the queen of cryptos change? The Flink home shopping delivery platform will be liquidated in France

The Flink home shopping delivery platform will be liquidated in France Bercy threatens to veto the sale of Biogaran (Servier) to an Indian industrialist

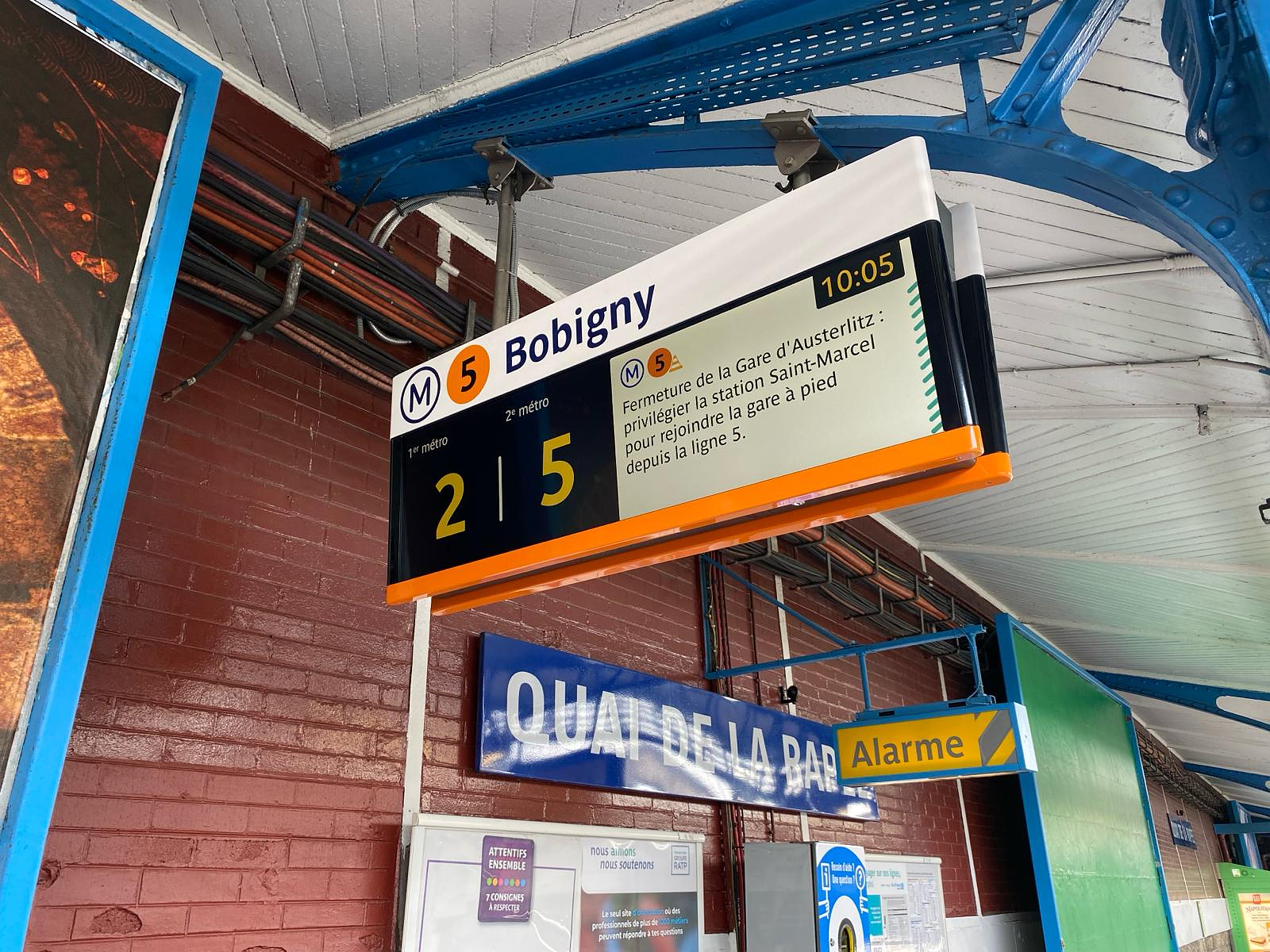

Bercy threatens to veto the sale of Biogaran (Servier) to an Indian industrialist Switch or signaling breakdown, operating incident or catenaries... Do you speak the language of RATP and SNCF?

Switch or signaling breakdown, operating incident or catenaries... Do you speak the language of RATP and SNCF? The main facade of the old Copenhagen Stock Exchange collapsed, two days after the fire started

The main facade of the old Copenhagen Stock Exchange collapsed, two days after the fire started Alain Delon decorated by Ukraine for his support in the conflict against Russia

Alain Delon decorated by Ukraine for his support in the conflict against Russia Who’s Who launches the first edition of its literary prize

Who’s Who launches the first edition of its literary prize Sylvain Amic appointed to the Musée d’Orsay to replace Christophe Leribault

Sylvain Amic appointed to the Musée d’Orsay to replace Christophe Leribault Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy

Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy During the night of the economy, the right points out the budgetary flaws of the macronie

During the night of the economy, the right points out the budgetary flaws of the macronie These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Europa Conference League: the semi-final flies to Lille, which loses to the wire against Aston Villa

Europa Conference League: the semi-final flies to Lille, which loses to the wire against Aston Villa Lille-Aston Villa: Cash disgusts Lille, the arbitration too... The tops and the flops

Lille-Aston Villa: Cash disgusts Lille, the arbitration too... The tops and the flops Handball: Les Bleues in the same group as Spain at Euro 2024

Handball: Les Bleues in the same group as Spain at Euro 2024 Europa Conference League: for Létang, Martinez “does not have the attitude of a high-level athlete”

Europa Conference League: for Létang, Martinez “does not have the attitude of a high-level athlete”