Nir Eyal screwed it up. A few years ago, the Israeli-American entrepreneur wanted to spend time with his daughter in a question-and-answer game. But just as she was telling him which superpower she would like to have, Eyal stopped listening - because he was on his smartphone, as the 42-year-old confessed in his blog: "'One second', I murmured, 'I have to be quick answer what...' When I looked up again, she was gone."

Eyal knew the pull of social media better than almost anyone else. He himself had created it. The Stanford graduate had risen to become the star of Silicon Valley with his behavioral design, a combination of psychology and technology. In talks and lectures, he explained to the industry how to create alluring devices and apps; his book "Hooked - How to create products that are addictive" became a bestseller. Until the incident with his daughter showed him that he himself was already wriggling on the hook.

Many Germans must have experienced the same thing as Nir Eyal. According to the ARD/ZDF online study, half of the population hangs around in social networks at least once a week; a fifth each visit Facebook and Instagram even daily. To like, share, pass the time - and in the knowledge that your own attention, productivity and mood often suffer as a result.

Nevertheless, some sink into the timeline as if in a trance; it's like all that fuss has reprogrammed the brain. This accusation is made against every new medium, but it is particularly persistent in the case of digitization; and not without reason, considering the episode with the expert Eyal. So what's with the fears? What does the use of social networks do with the gray matter?

“Our everyday experiences leave traces in the brain. This also includes the online activities that we pursue,” says Christian Montag. The psychologist from the University of Ulm has been investigating how digitization affects the human brain for more than a decade. "Our brains are very adaptable," he says. If it is confronted with unfamiliar influences or demands, it reacts by forming new connections between individual nerve cells or entire brain regions.

This neuroplasticity can also be observed when dealing with digital media: In 2014, the neuroscientist Arko Ghosh demonstrated in "Current Biology" that daily tapping and swiping on the smartphone screen remodels the sensorimotor cortex and influences the sensory processing of the brain.

"But the same thing happens when you play the violin or learn to juggle," says Montag. "And these newly created nerve pathways can also regress if you don't perform the movements for a long time."

But does the use of social networks also influence cognitive functions – how we think, feel, act? "There's no general answer to that," says Montag. Many factors played a role: What personality does a person have, what background does he come from, how satisfied is he? How often and how long is he on the platforms, does he participate or let himself be showered, and what is he watching? Whether it's young girls posting dance videos on TikTok or comparing themselves to anorexics on Instagram, that's an important distinction for Montag.

Despite all the differences, there is also typical behavior: for example, that people post everyday experiences or hand out little hearts and thumbs up. A number of studies have examined what happens in the brain, with the result that the relevant activities lead to certain neuronal circuits activating or even being created anew.

The psychologist Lauren Sherman was able to show that the reward system of Facebook users is not only activated when they receive likes, but also when they give them some. And neuroscientist Dar Meshi uncovered a network of brain areas that activate when people share information about themselves on Facebook; the stronger the neural network, the more they revealed about themselves.

However, it is not easy to make such changes visible at all with imaging processes. The study that researchers at the University of North Carolina published in the journal "Jama Pediatrics" at the beginning of January is therefore all the more remarkable. The team led by psychologist Eva Telzer wanted to find out whether the brains of young people who regularly opened Facebook, Instagram and Snapchat developed differently than those of their peers who rarely visited these platforms.

To do this, they pushed 169 sixth and seventh graders into the MRI tube for three years in a row for a reaction test that imitated the sometimes incalculable sense of achievement and disappointment on social media; the device measured the activity of the brain areas based on the changed blood flow. In fact, the researchers found that the brains developed differently in the areas responsible for motivation, directed attention, and cognitive control.

In the case of very regular users, these brain regions were initially less active, but all the more so after three years. The opposite was true for irregular users. According to Telzer and her team, this suggests that teens who rarely use social media become better at controlling habitual or impulsive behaviors -- like checking apps -- over time, while "heavy users" have less ability to resist this urge.

The psychologist Christian Montag considers the study to be "remarkable". However, questions remained unanswered: Are these changes in the brain permanent? Do they affect the psyche and behavior of 12 to 15 year olds? And are the findings easily transferrable to adults? "Especially in puberty, the reward system can be strongly influenced," says Martin Korte, neurobiologist at the Technical University of Braunschweig.

Korte is also researching how digital media affect the brain; primarily on processes of learning and remembering. In youth, the organ learns particularly quickly to link neutral stimuli or actions with positive or negative experiences.

“This reward learning works with addictive substances. Or with social signals in the form of emojis.” Anyone who receives a like feels recognized and liked. The result: the brain releases dopamine, the "messenger of happiness". And because you expect to get new likes with every detour, checking becomes a habit.

Adults are also receptive to the dopamine kick of colorful pictures. It's not for nothing, says Korte, that you can react with emojis or funny mini-clips in professional messenger services like Microsoft Teams: "It's the same principle." In addition, platforms like Facebook often display the likes with a delay and thus lure their users : "It's like the one-armed bandit in the casino," says Korte. "You feel like you could win with every post, but you don't always win."

The neurobiologist is not only concerned with what triggers social media in people's brains - but also what they prevent them from doing. A study by the University of Bath found that users who seek distraction on the platforms prevent themselves from entering a state of deeper boredom. "But this boredom is an important prerequisite for creativity," says Korte. Only then does the brain go into a kind of mental idle state, in which it is particularly good at coming up with ideas or finding solutions.

Even memory performance is influenced by social networks: Psychologists from the University of Michigan demonstrated in 2020 that users, regardless of their age, had larger memory gaps after days of extensively playing on the platforms. And the following year, British psychologist Andrew Johnson was able to prove that people remember experiences better when they shared them online. Korte finds this problematic because such posts usually show a filtered, embellished version of one's own life - and could distort memory.

Disturbing as all these findings may seem, they should be interpreted with caution. The MRI studies in particular provide impressive evidence of a change in the brain. But: "We can only interpret how such changes in neuronal activity patterns affect everyday life and mental performance of a person based on the affected areas," says Ulm psychologist Montag.

"Or by using self-reports to record what changes the test subjects themselves notice and draw conclusions from them." The decisive factor is not necessarily how long someone is on the screen, but how much they suffer from social media; for example because, like the entrepreneur Nir Eyal, he notices a lack of concentration and a loss of control.

The question remains: what can be done about it? Neither Montag nor Korte believe in “digital detox” as a permanent solution. Instead, both list tips and tricks on how to escape the pull; for example by getting used to wearing a watch (see chapter at the end of the text). But, says Montag: "As long as people pay for use with their data, the developers will do everything to keep them tied to the platforms for as long as possible." Basically, a different business model was needed, possibly with social networks than public good.

And Nir Eyal? He already has a new business model. Five years after the bestseller about addictive tech products, he published his second book in 2019, about the "superpower of the future". It's called: "The art of not being distracted".

"Aha! Ten minutes of everyday knowledge" is WELT's knowledge podcast. Every Tuesday and Thursday we answer everyday questions from the field of science. Subscribe to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Deezer, Amazon Music, Google Podcasts or directly via RSS feed.

______

Digital experts recommend using social media consciously. With mobile phones, but also apps, usage times can be recorded – and limits can be set. Push notifications, read receipts, and ringtones should remain off. In black and white mode, app icons and social media content are less enticing. Anyone who sets the analog alarm clock and wears a wristwatch reaches for their smartphone less often. And inhibitions such as time-consuming unlocking or tedious logging in via browser make constant checking more difficult.

The Smart@net app, which the Ulm psychologist Christian Montag developed with colleagues, helps against the feeling of not having your own network use under control. Everyone can use it to check free of charge whether their online behavior is conspicuous - and, depending on their needs, receive tips on prevention or assistance on how to counteract this, through to advice and therapy offers.

His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction

His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial?

Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial? What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain?

What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain? The shadow of Chinese espionage hangs over Westminster

The shadow of Chinese espionage hangs over Westminster Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50

Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50 H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States

H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated)

What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated) Vaccination in France has progressed in 2023, rejoices Public Health France

Vaccination in France has progressed in 2023, rejoices Public Health France The right deplores a “dismal agreement” on the end of careers at the SNCF

The right deplores a “dismal agreement” on the end of careers at the SNCF The United States pushes TikTok towards the exit

The United States pushes TikTok towards the exit Air traffic controllers strike: 75% of flights canceled at Orly on Thursday, 65% at Roissy and Marseille

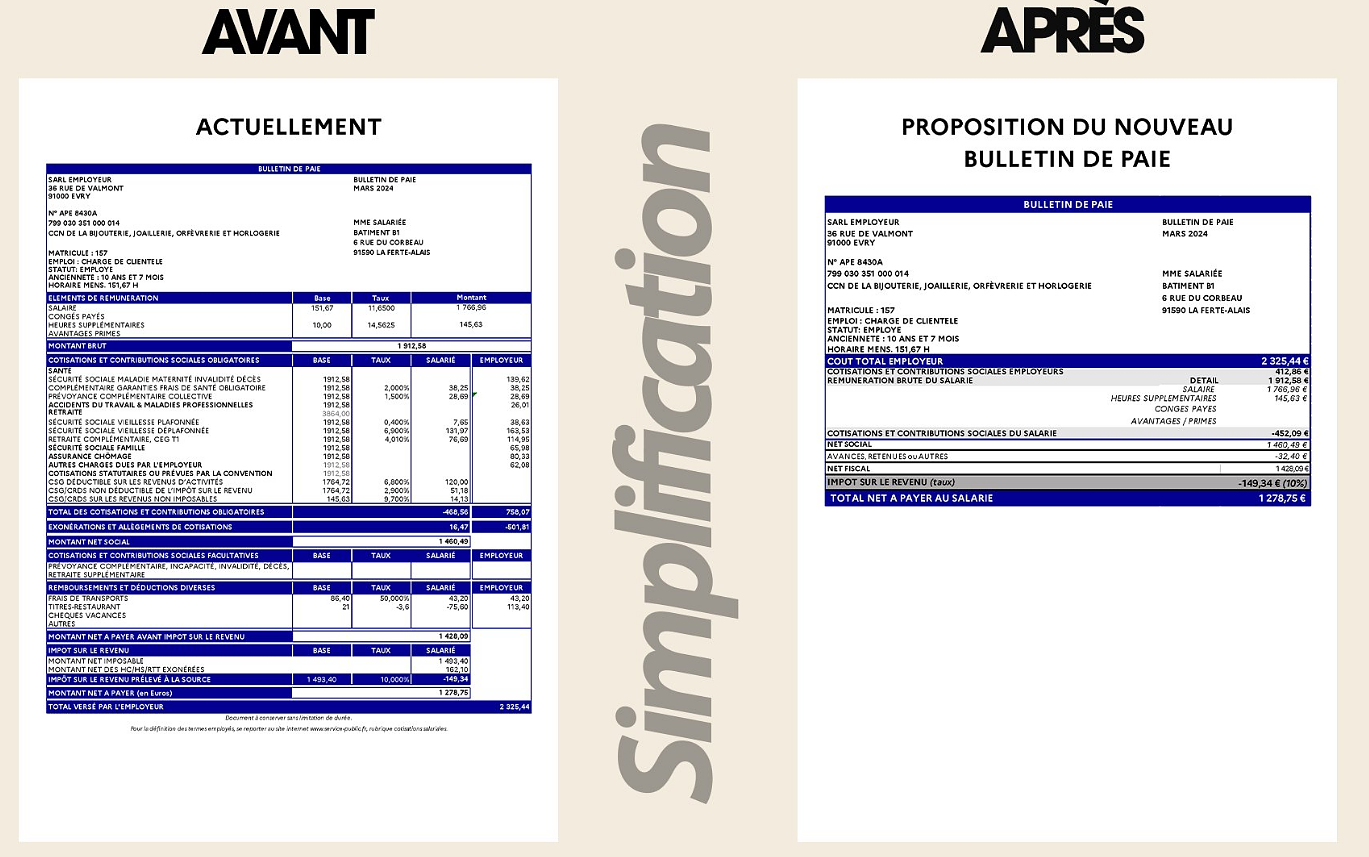

Air traffic controllers strike: 75% of flights canceled at Orly on Thursday, 65% at Roissy and Marseille This is what your pay slip could look like tomorrow according to Bruno Le Maire

This is what your pay slip could look like tomorrow according to Bruno Le Maire Sky Dome 2123, Challengers, Back to Black... Films to watch or avoid this week

Sky Dome 2123, Challengers, Back to Black... Films to watch or avoid this week The standoff between the organizers of Vieilles Charrues and the elected officials of Carhaix threatens the festival

The standoff between the organizers of Vieilles Charrues and the elected officials of Carhaix threatens the festival Strasbourg inaugurates a year of celebrations and debates as World Book Capital

Strasbourg inaugurates a year of celebrations and debates as World Book Capital Kendji Girac is “out of the woods” after his gunshot wound to the chest

Kendji Girac is “out of the woods” after his gunshot wound to the chest Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy

Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar NBA: the Wolves escape against the Suns, Indiana unfolds and the Clippers defeated

NBA: the Wolves escape against the Suns, Indiana unfolds and the Clippers defeated Real Madrid: what position will Mbappé play? The answer is known

Real Madrid: what position will Mbappé play? The answer is known Cycling: Quintana will appear at the Giro

Cycling: Quintana will appear at the Giro Premier League: “The team has given up”, notes Mauricio Pochettino after Arsenal’s card

Premier League: “The team has given up”, notes Mauricio Pochettino after Arsenal’s card