Even the perpetrator himself had lost all idea of the magnitude of his crimes. When on the morning of April 15, 1946, the former commandant of the Auschwitz concentration and extermination camp, Rudolf Höß, stood as a witness before the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg, he confirmed that “every word of an affidavit of his own that was read out in court , be true,” reported WELT.

Höss, according to the reporter's impression "a small, stocky man with narrow eyes", thus admitted to outrageousness. Because after a previous interrogation, he had authenticated an abridged summary with his signature: “I headed the Auschwitz camp from 1. May 1940 to December 1, 1943 and estimate that at least two and a half million people perished through gassing or incineration and were exterminated. At least half a million more died from starvation and disease, bringing the total dead to three million. This number represents approximately 70 to 80 percent of all persons who were sent to Auschwitz as prisoners.”

A few days later, however, Höss noted in his own hand that the estimate of 2.5 million victims of the murder factory in German-occupied East Upper Silesia was the number that the deportation expert Adolf Eichmann had given him. The former Auschwitz commandant now recalled significantly lower numbers, totaling 1.125 million - as if that were any better than just a tad less monstrous.

Six weeks after the testimony in Nuremberg, Höss was flown to Warsaw via Berlin so that he could be tried in the country where the crime scene of his outrageous crimes was located. The Kraków lawyer Jan Sehn (1909 to 1965) had pushed for this. "In accordance with the principles of forensic science, he divides himself into four and five in order to quickly secure the greatest possible amount of evidence," a long-time employee later recalled of his boss.

Jan Sehn was undoubtedly the driving force behind the Nazi trials in Poland. As an examining magistrate, a function not customary in German law, he prepared not only the proceedings against Höß in 1947 but also the trial against the commandant of the Plaszow concentration camp Amon Göth, today best known as Oskar Schindler's antagonist in Steven Spielberg's film "Schindler's List". . Then there was the great Auschwitz trial in Kraków in 1947, in which 39 of the 40 accused were found guilty, and the trial of Josef Bühler, the state secretary in the administration of the “General Government”, as central Poland was called during the German occupation.

The Warsaw historian Filip Gańczak dedicated a biography to Sehn, which has now also been published in German (Wallstein-Verlag Göttigen. 238 p., 26 euros). The employee of the Polish investigation authority IPN (Instytut Pamięci Narodowej), which both prepares indictments and conducts historical research, describes the life and work of that man without whom there would be far less knowledge about Auschwitz. Sehn is important for the Federal Republic because he prepared the first Frankfurt Auschwitz trial in close cooperation with Hesse's Attorney General Fritz Bauer.

Which of these processes was the most important can hardly be judged seriously - each had its own significance. In any case, on March 11, 1947, the trial against Höss began in Warsaw. The Supreme Court had already ruled in January: “Only the camp commander, Rudolf Höß, will stand before the tribunal. The trial of about a hundred camp staff members will take place at a later date in the District Court in Kraków.”

On February 21, 1947, the Chief Public Prosecutor had asked the examining magistrate Sehn to quickly present all the evidence relevant to the indictment. "What Sehn has compiled is impressive, but he keeps adding more and more," writes Gańczak.

The prosecution was essentially based on Sehn's material. Höss was accused of being the commander of Auschwitz, responsible for the inhumane conditions there, the torture of countless prisoners and an unknown number of murders. A separate section in the indictment dealt with his role in the mass murder in the Birkenau gas chambers. Other allegations related to the organization of slave labor for the purpose of exploitation and the theft of the deportees' property.

Hoess was of course aware of his hopeless situation; there could only be the maximum penalty for his crimes. In view of the clear evidence, he refrained from a real defense and only tried to make minor corrections to the indictment and the statements of witnesses.

In fact, Sehn had made a mistake: He stuck to his statement from the end of September 1946 that “no fewer than four million people” had been gassed and cremated in Auschwitz. So the 2.5 million mentioned by Höß in Nuremberg between 1940 and 1943 and another one and a half million in 1944 during the mass deportations of Hungarian Jews.

In the interrogations that Sehn conducted with Höß in the course of his investigations, the former concentration camp commandant spoke of “millions of people” who had been gassed – he couldn’t remember more precisely. It was only at the trial that he testified that the number had not been higher than one and a half million, i.e. about the value that he had given in his handwritten note from the end of April 1946.

Was that a deliberate confusion tactic? Was Höss trying to undermine the credibility of the prosecution? It was clear that the dispute over the number of victims would not change the verdict. Neither does the momentary pang of remorse when he admitted “that I went down the wrong path. Through my participation in the actions of the organization I belonged to, which I described, I became an accomplice in the evil that burdens this organization.” Jan Sehn commented on this vague formulation: “In all of Höss's statements, however, there is no admission of his personal guilt. "

The verdict was not really surprising: on April 2, 1947, the judges found Rudolf Höß guilty as charged and imposed the maximum penalty: execution. Of course, Poland's President Bolesław Bierut, an evil Stalinist, did not exercise his right to pardon, and so on the morning of April 16, 1947, Rudolf Höss returned to Auschwitz for the last time.

Jan Sehn, although an opponent of the death penalty himself, was present that morning. His colleague Krystyna Szymanska recalled the preparations for Höss's execution: "They had built a gallows for him that looked like the gallows in the camp had looked like. They didn't want to hang him on one of the gallows from which the prisoners had previously been hanged."

She did not follow the last moments in the life of the mass murderer Rudolf Höß with her own eyes: “I saw how he went to the place of execution. I then ran to the other end of the camp - I couldn't see it. From the reports of eyewitnesses I know that the convict traveled this path completely calmly until the last moment.” In fact, the former concentration camp commandant remained completely calm and did not express any last wishes, as confirmed by the public prosecutor who carried out the sentence supervised.

In his farewell letter to his wife, Höss wrote: “I only got to know what humanity is here in the Polish prisons. I, who, as the commander of Auschwitz, caused so much harm and suffering to the Polish people, was met with a humane understanding that often and often deeply shamed me.” The historian Filip Gańczak concludes: “It can be assumed that these words also related to Jan Sehn.”

You can also find "World History" on Facebook. We are happy about a like.

Germany: the trial of an AfD leader, accused of chanting a Nazi slogan, resumes this Tuesday

Germany: the trial of an AfD leader, accused of chanting a Nazi slogan, resumes this Tuesday New York: at Columbia University, the anti-Semitic drift of pro-Palestinian demonstrations

New York: at Columbia University, the anti-Semitic drift of pro-Palestinian demonstrations What is Akila, the mission in which the Charles de Gaulle is participating under NATO command?

What is Akila, the mission in which the Charles de Gaulle is participating under NATO command? Lawyer, banker, teacher: who are the 12 members of the jury in Donald Trump's trial?

Lawyer, banker, teacher: who are the 12 members of the jury in Donald Trump's trial? What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated)

What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated) Vaccination in France has progressed in 2023, rejoices Public Health France

Vaccination in France has progressed in 2023, rejoices Public Health France Food additives suspected of promoting cardiovascular diseases

Food additives suspected of promoting cardiovascular diseases “Even morphine doesn’t work”: Léane, 17, victim of the adverse effects of an antibiotic

“Even morphine doesn’t work”: Léane, 17, victim of the adverse effects of an antibiotic Orthodox bishop stabbed in Sydney: Elon Musk opposes Australian injunction to remove videos on X

Orthodox bishop stabbed in Sydney: Elon Musk opposes Australian injunction to remove videos on X One in three facial sunscreens does not protect enough, warns L'Ufc-Que Choisir

One in three facial sunscreens does not protect enough, warns L'Ufc-Que Choisir What will become of the 81 employees of Systovi, a French manufacturer of solar panels victim of “Chinese dumping”?

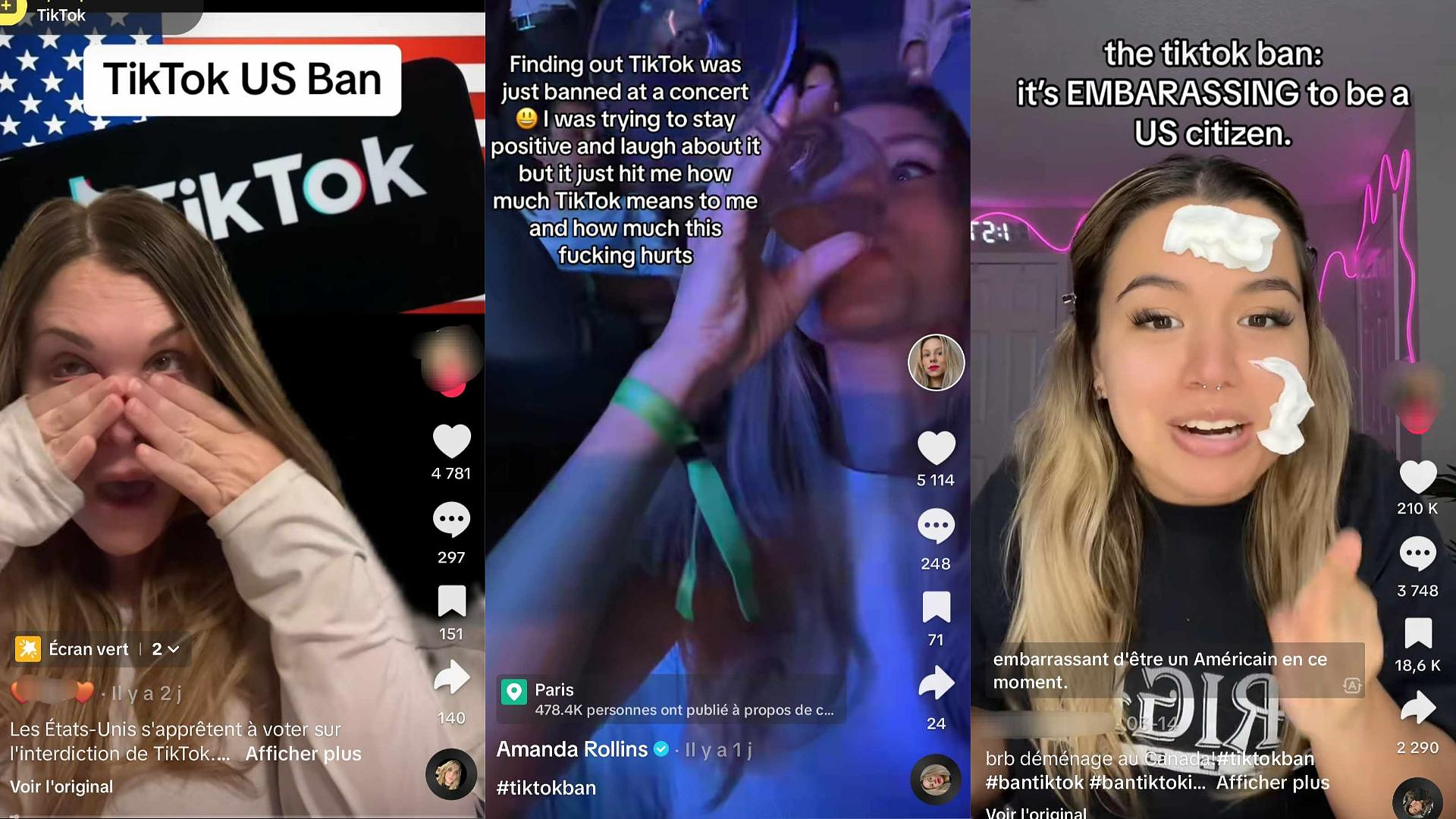

What will become of the 81 employees of Systovi, a French manufacturer of solar panels victim of “Chinese dumping”? “I could lose up to 5,000 euros per month”: influencers are alarmed by a possible ban on TikTok in the United States

“I could lose up to 5,000 euros per month”: influencers are alarmed by a possible ban on TikTok in the United States Dance, Audrey Hepburn’s secret dream

Dance, Audrey Hepburn’s secret dream The series adaptation of One Hundred Years of Solitude promises to be faithful to the novel by Gabriel Garcia Marquez

The series adaptation of One Hundred Years of Solitude promises to be faithful to the novel by Gabriel Garcia Marquez Racism in France: comedian Ahmed Sylla apologizes for “having minimized this problem”

Racism in France: comedian Ahmed Sylla apologizes for “having minimized this problem” Mohammad Rasoulof and Michel Hazanavicius in competition at the Cannes Film Festival

Mohammad Rasoulof and Michel Hazanavicius in competition at the Cannes Film Festival Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy

Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Serie A: Bologna surprises AS Rome in the race for the C1

Serie A: Bologna surprises AS Rome in the race for the C1 Serie A: Marcus Thuram king of Italy, end of the debate for the position of number 9 with the Blues?

Serie A: Marcus Thuram king of Italy, end of the debate for the position of number 9 with the Blues? Milan AC-Inter Milan: Thuram and Pavard impeccable, Hernandez helpless… The tops and flops of the derby

Milan AC-Inter Milan: Thuram and Pavard impeccable, Hernandez helpless… The tops and flops of the derby Ligue 2: Auxerre leader, Bordeaux in crisis, play-offs... 5 questions about an exciting end of the season

Ligue 2: Auxerre leader, Bordeaux in crisis, play-offs... 5 questions about an exciting end of the season