Nobody knows how everything would have happened if there hadn't been so much snow in the Celle area on January 9, 1972. But that's how jersey advertising came to the Bundesliga - and with it a million-dollar business. It actually came in the mail, and the messenger is proud of it to this day. Klaus-Dieter Seisselberg (76) from Wienhausen (Lower Saxony) calls himself the “only inventor/introducer of sports advertising in Germany”. The fame so far has been the multi-millionaire entrepreneur Günter Mast († 84), managing director of the liqueur manufacturer Jägermeister, who joined Eintracht Braunschweig in 1973 and caused the DFB a lot of trouble.

But that's only half the truth, because Mast got the idea from the postman. And that's how it happened: At the post office, Seisselberg came across an express letter to Mast, which his colleagues should have brought to Mast's remote property near Lutterloh (Lower Saxony). But the village postmen of the 1970s were all still on their bikes – “and because I had to drive the tour up there in my mail truck anyway, I wanted to relieve my colleagues.” Seisselberg’s extra tour ultimately wrote football history. Only on his deathbed did Mast Seisselberg, who died in 2011, give the go-ahead for the true version: "Mr. Seisselberg, tell the press now how the shirt advertising came about - and say that you were the one who made me to implement this."

At that time, Seisselberg was invited into the apartment by Mast, who was surprised that an express letter had come with the van. They drank a schnapps and became friends. Seisselberg asked the influential man if he could do something for his roller hockey club. According to Seisselberg, the ultimately sports-historical proposal was as follows: "Mr. Mast, if you would support our roller hockey department, I would even wear your Jägermeister deer and your logo lettering on my chest."

Mast replied: "Mr. Seisselberg, that's the Hubertus deer!" He gave him a five-mark piece and a Jägermeister to thank him for the delivery, and then they exchanged addresses and telephone numbers. Although it wasn't about football at first, the idea of shirt advertising was now in Mast's mind. It wasn't long before he thought of expanding it into more attractive sports. As early as 1972, an ice hockey club called SC Jägermeister was in Italy's second division.

Mast now had the idea of entering the Bundesliga. Eintracht Braunschweig was the biggest club on his doorstep. Because he knew President Ernst "Balduin" Fricke († 71) well, he made the master of 1967 an immoral offer. Immoral because shirt advertising was banned in the first Bundesliga decade. The players were allowed to advertise chocolate bars, hairspray or sports equipment suppliers privately, and the clubs were already selling their gangs – but the playing clothes had to remain advertising-free. The DFB did not want any walking advertising pillars, which it expressly decided at the Bundestag in 1967 - because regional league club Wormatia Worms had dared to advertise three times for a local construction machinery company.

Eintracht knew the attitude of the DFB, but like almost all clubs, it was in debt and urgently needed money - income was only generated through audience money, perimeter advertising and television, which paid 127,000 DM per club.

Due to the Bundesliga scandal of 1971 (postponed games in the relegation battle) the stadiums were empty like never before. And now Mast came along and offered Eintracht 500,000 DM – for a five-year contract. Fricke: "When our members found out about it, they were ready to paint a whole zoo on their shirt."

Eintracht reached an agreement with Mast as early as April 1972 and the debt was cleared in one fell swoop. The fact that Mast, who even became president of the club in 1983, had no idea about football didn't bother anyone. He only saw it as a platform for his business. "I haven't seen a game for 32 years, but now I have to go to my Eintracht players," he said. When he came into the dressing room at half-time, coach Branko Zebec († 59) threw him out: "This is my area, Mr. Mast!" That was when the deer was long on the jersey. But how did he get there?

With a trick. The months that followed became one big posse. It began on January 8, 1973: by changing the statutes - with 145:7 member votes with three abstentions - the club's coat of arms was changed and the Hubertus deer replaced the lion, the city's heraldic animal. President Fricke said: "The amendment to the statutes is entered in the register of associations, and no instance can do anything against association law."

In the home game against Kickers Offenbach on January 27, 1973, the deer was to have its premiere. The jerseys were freshly printed, but they were never used. Because the day before, the DFB league committee sent a telegram and expressly warned Eintracht against using them. Referee Walter Eschweiler (86) received instructions not to whistle the game if Eintracht arrived "not in proper playing attire".

This includes that no coat of arms may be larger than 14 centimeters. What happened next was often misrepresented – also by Eschweiler: the cult referee pulled out his tape measure and gave permission to play with the words: “Sit, fit, wobble and have air.” According to this, this game was the premiere of jersey advertising been. But that's not true – the new Eintracht jersey wasn't even used in the game – as match photos and press reports show. Bernd Franke (74), then in the Eintracht goal, confirmed in an interview with SPORT BILD that the deer remained in the enclosure: "Eschweiler always talked a lot, even on the pitch. He is wrong, there was no measuring tape.”

So the premiere was cancelled, but there was a lot of excitement, which could only be Mast. The Jägermeister name was constantly in the media, and Mast was delighted – for so much publicity he would have had to invest twenty times more in advertising than in the contract with Eintracht. The dispute dragged on for months. Because Eintracht had to be careful not to spoil things with the DFB. The reason: In February, almost all players were before the sports court because they had accepted a prize money from a third party in the scandal year 1971. For this they were provisionally suspended for three months and then pardoned (fine 4400 DM).

The Franconian, who was not affected by this, remembers: “Back then we could only train with four professionals, the others were in Frankfurt every two weeks. That's why we were relegated.” So the deer didn't bring any luck, the founding member had to be in the second division for the first time in 1973/74.

But how did it go on with the jersey issue? The premiere was postponed several times. For the home game against Oberhausen (February 10), the deer was the prescribed maximum size, but the letters “EB” (for Eintracht Braunschweig), which the DFB insisted on, were said to be too small. On February 26, the DFB then gave Eintracht permission to play with the deer. But it lasted until March 24th. Until then, Braunschweig played without a coat of arms or with the old jerseys because the embroidery commissioned was overwhelmed with the constant new instructions and couldn't get the new jerseys ready in time.

On March 24, 1973 in a home game against Schalke (1:1) was the Hirsch premiere. Gritting their teeth, the DFB had to give in, even if it hadn't officially approved the advertising - just a new coat of arms. There was also nothing to read about "Jägermeister" against Schalke - in contrast to the jerseys of Seisselberg's roller hockey club, which premiered in January 1973. But the case had caused such a stir that now everyone knew what the deer stood for. In fact, Mast had circumvented the advertising ban, a taboo was broken - and suddenly 1. FC Nuremberg played in the regional league with AEG. The television stations were up in arms about the "surreptitious advertising". So something had to be done.

On June 19, 1973, DFB general secretary Hans Paßlack († 76), one of Mast’s most determined opponents (“He’s turning our Bundesliga into a pub”), sent a circular to his board and suggested the “formation of a commission to examine the problem advertising on sportswear”. He remarked, "...that there is a trend in which public opinion is developing in the direction that advertising in sport is useful and therefore no longer to be rejected." He anticipated the result that the DFB Bundestag announced on 27 October 1973 decided.

Jersey advertising was permitted, but "the principles of ethics and morals must be observed." A company emblem could take up a maximum of 170 square centimeters, lettering 8 x 25 centimeters (rectangular). Millions have flowed into the coffers of the Bundesliga clubs every year since then. FC Bayern currently receives around 50 million euros per season from Telekom. And television, which was once so hostile, places more advertising around the broadcasts than the clubs themselves. All because of the postman Seisselberg's extra tour.

The article was written for the sports competence center (WELT, "Sport Bild", "Bild") and first published in "Sport Bild".

New York: at Columbia University, the anti-Semitic drift of pro-Palestinian demonstrations

New York: at Columbia University, the anti-Semitic drift of pro-Palestinian demonstrations What is Akila, the mission in which the Charles de Gaulle is participating under NATO command?

What is Akila, the mission in which the Charles de Gaulle is participating under NATO command? Lawyer, banker, teacher: who are the 12 members of the jury in Donald Trump's trial?

Lawyer, banker, teacher: who are the 12 members of the jury in Donald Trump's trial? After 13 years of mission and seven successive leaders, the UN at an impasse in Libya

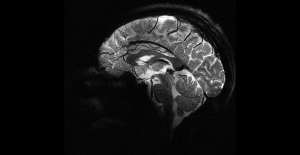

After 13 years of mission and seven successive leaders, the UN at an impasse in Libya What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated)

What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated) Vaccination in France has progressed in 2023, rejoices Public Health France

Vaccination in France has progressed in 2023, rejoices Public Health France Food additives suspected of promoting cardiovascular diseases

Food additives suspected of promoting cardiovascular diseases “Even morphine doesn’t work”: Léane, 17, victim of the adverse effects of an antibiotic

“Even morphine doesn’t work”: Léane, 17, victim of the adverse effects of an antibiotic Orthodox bishop stabbed in Sydney: Elon Musk opposes Australian injunction to remove videos on X

Orthodox bishop stabbed in Sydney: Elon Musk opposes Australian injunction to remove videos on X One in three facial sunscreens does not protect enough, warns L'Ufc-Que Choisir

One in three facial sunscreens does not protect enough, warns L'Ufc-Que Choisir What will become of the 81 employees of Systovi, a French manufacturer of solar panels victim of “Chinese dumping”?

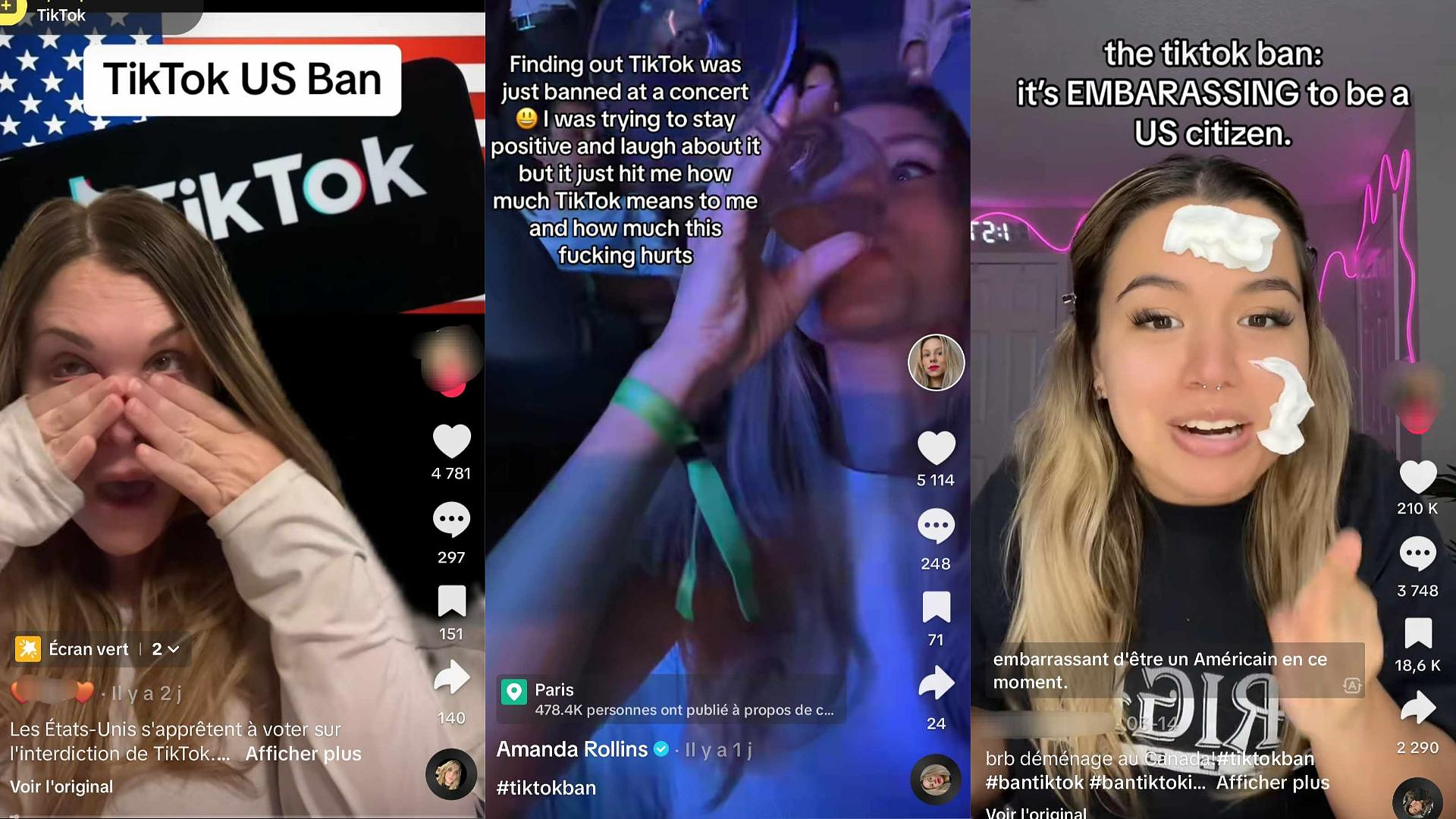

What will become of the 81 employees of Systovi, a French manufacturer of solar panels victim of “Chinese dumping”? “I could lose up to 5,000 euros per month”: influencers are alarmed by a possible ban on TikTok in the United States

“I could lose up to 5,000 euros per month”: influencers are alarmed by a possible ban on TikTok in the United States Dance, Audrey Hepburn’s secret dream

Dance, Audrey Hepburn’s secret dream The series adaptation of One Hundred Years of Solitude promises to be faithful to the novel by Gabriel Garcia Marquez

The series adaptation of One Hundred Years of Solitude promises to be faithful to the novel by Gabriel Garcia Marquez Racism in France: comedian Ahmed Sylla apologizes for “having minimized this problem”

Racism in France: comedian Ahmed Sylla apologizes for “having minimized this problem” Mohammad Rasoulof and Michel Hazanavicius in competition at the Cannes Film Festival

Mohammad Rasoulof and Michel Hazanavicius in competition at the Cannes Film Festival Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

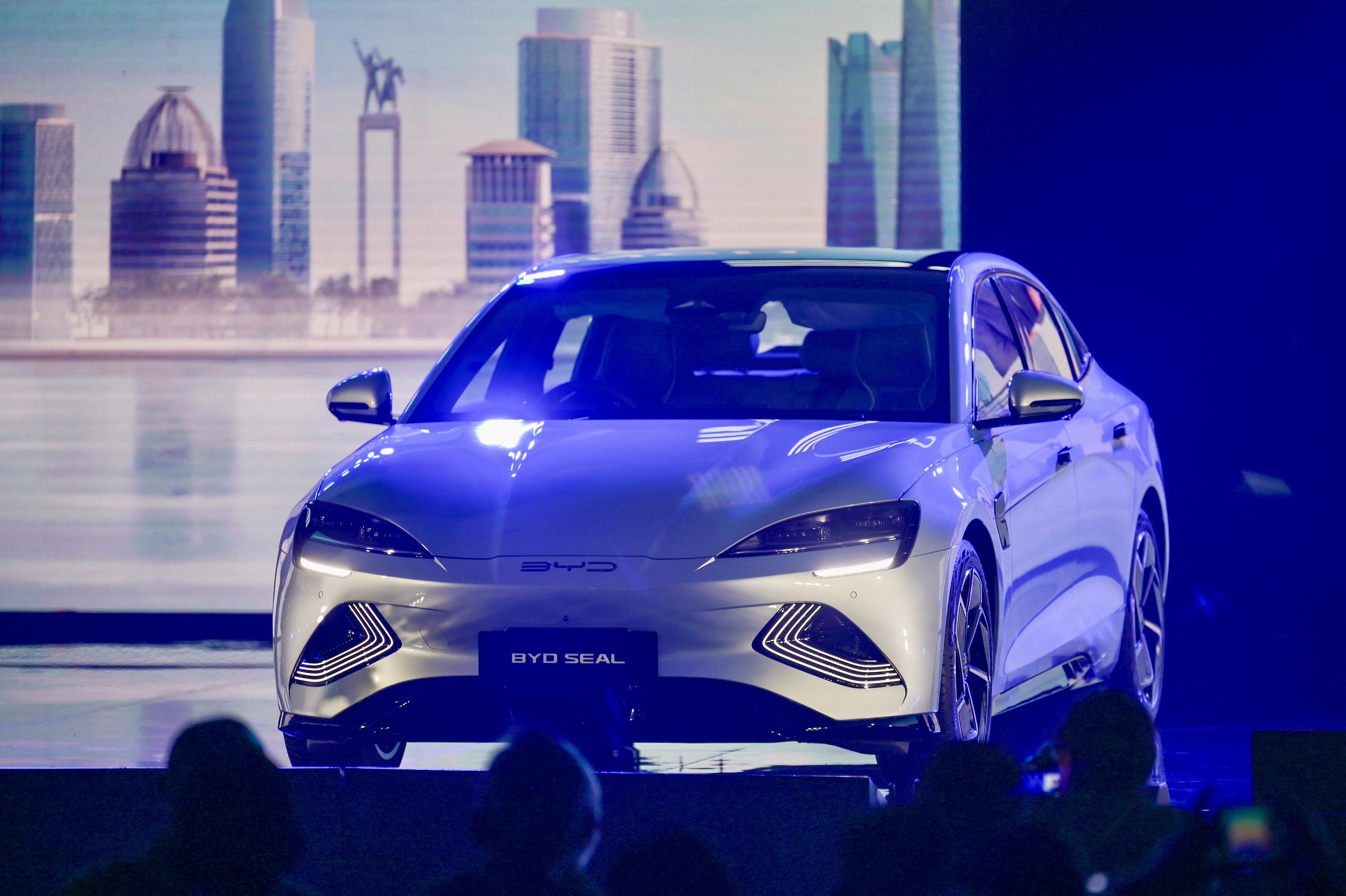

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy

Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Basketball (F): big winner of Asvel, Basket Landes will face Tarbes in the semi-final of the League

Basketball (F): big winner of Asvel, Basket Landes will face Tarbes in the semi-final of the League Football: Yazici (Lille) “in shock” after an attempted theft at his home

Football: Yazici (Lille) “in shock” after an attempted theft at his home Serie A: victorious over AC Milan, Inter crowned Italian champions for the 20th time

Serie A: victorious over AC Milan, Inter crowned Italian champions for the 20th time Serie A: “Winning a title in a derby has never happened,” relishes Martinez after Inter’s coronation

Serie A: “Winning a title in a derby has never happened,” relishes Martinez after Inter’s coronation