Bavaria's hour struck when, on May 23, 1618, two imperial councilors and a secretary were thrown out of a room in Prague Castle by angry nobles. In order to be able to counter the rebellious estates of his Bohemian kingdom, Emperor Ferdinand II needed an army. But he didn't have that, and his coffers were empty, as always.

Duke Maximilian of Bavaria (1573 to 1651) had been waiting for this opportunity for a long time. Ever since he came to power in 1597, his goals had been to increase Bavarian power and re-Catholicize the empire; he had consistently worked toward this. After the Prague Defenestration, he was the only one among the Catholic imperial princes who had enough means and a powerful army to help the emperor. Maximilian gambled for more than a year, then Ferdinand reluctantly agreed to sign the contract in Munich on October 8, 1619, which contained the Wittelsbacher's maximum demands.

Posterity, especially Protestants, did not give Maximilian a good hair. Leopold von Ranke, the historian of the Prussian state, characterized him as a Jesuit Machiavellian with a head full of adventures. It took a long time for people to realize that Maximilian was a hands-on reformer and Realpolitiker who made early modern Bavaria the best-managed territorial state in the empire. It is not for nothing that he is now regarded as “probably the greatest of all Wittelsbachers”.

However, luck was on his side. His two predecessors had largely disempowered the Estates and solved the Protestant problem by rigorously stopping the Reformation. Maximilian, who was already acting as co-regent at the side of his father Wilhelm V at the age of 21, had recognized in good time that chronic underfinancing was the Achilles heel of all courts: “A prince who is not rich in this evil world, het khein authoritet nor reputation,” he explained the basic motive of his policy.

Therefore, despite his unstable health and hours of prayer exercises a day, he forced himself “to look at my things myself, read the bills myself, and whatever I found, sanded, took a report on, and remedied the things”. In this sense, he created a bureaucratic apparatus whose members were not given their posts by purchase or patronage, but were recruited on the basis of education and competence.

This gave Maximilian the financial leeway to maintain an army, which in turn made Bavaria an attractive partner for smaller Catholic principalities in the empire. In July 1609 the League was founded in Munich as a defensive alliance to defend Catholic interests. It saw itself as the counterpart to the Protestant Union, which, however, suffered from the internal opposition between Lutherans and Reformed.

The league also had a structural problem: the Habsburgs wanted to sideline the Wittelsbacher. Maximilian then resigned the presidency in 1616. However, when the signs pointed to war after the defenestration of Prague, he quickly succeeded in reviving the alliance. And he presented a general of international stature: Johann Tserclaes Tilly.

Time now played into Maximilian's hands. On August 26, 1619, the Bohemian Estates elected the Reformed Count Palatine and Elector Friedrich V as King of Bohemia. This was a declaration of war against the Habsburg Ferdinand II, who had worn the crown since 1617 and who had also ruled the Austrian hereditary lands since the death of Emperor Matthias in March 1619. On September 9th of that year he was elected the new emperor - even with the votes of the Palatinate - after Maximilian had been clever enough to refuse his candidacy. This gave Ferdinand the legitimation to take action against Bohemia, but no army.

In this situation, the new Kaiser made a stop in Munich on the return journey from Frankfurt. It was now easy for Maximilian to get Ferdinand's signature on the contract. In it, the Bavarian was confirmed as head of the league and "right hand man" of the Kaiser, which gave Maximilian considerable freedom. Should the league army of 18,000 soldiers and 2,600 horsemen be used outside the alliance, the emperor would pay for the financing. He would also compensate for Bavarian territorial losses with Austrian areas. Maximilian's wages were not recorded in writing: he was to keep his conquests and, in the event of a victory over Frederick of Bohemia, receive the Palatinate electoral dignity.

That was enough motivation for Maximilian. On November 8, 1620, the imperial league troops under Tilly's leadership - Maximilian was only formally in command - defeated the Bohemians on the White Mountain in front of Prague. Further successes ended the threat posed by the Protestants and allowed Ferdinand II to develop his vision of a re-Catholicisation of the empire. As a thank you, the Bavarian received the Oberpfalz in addition to the electoral dignity.

However, the intervention of Gustav II Adolf of Sweden in 1630 saved the Protestants. And from now on, Bavaria also became a battlefield.

You can also find "World History" on Facebook. We are happy about a like.

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction

His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial?

Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial? What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain?

What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain? Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50

Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50 H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States

H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation

Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application

Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application “I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing

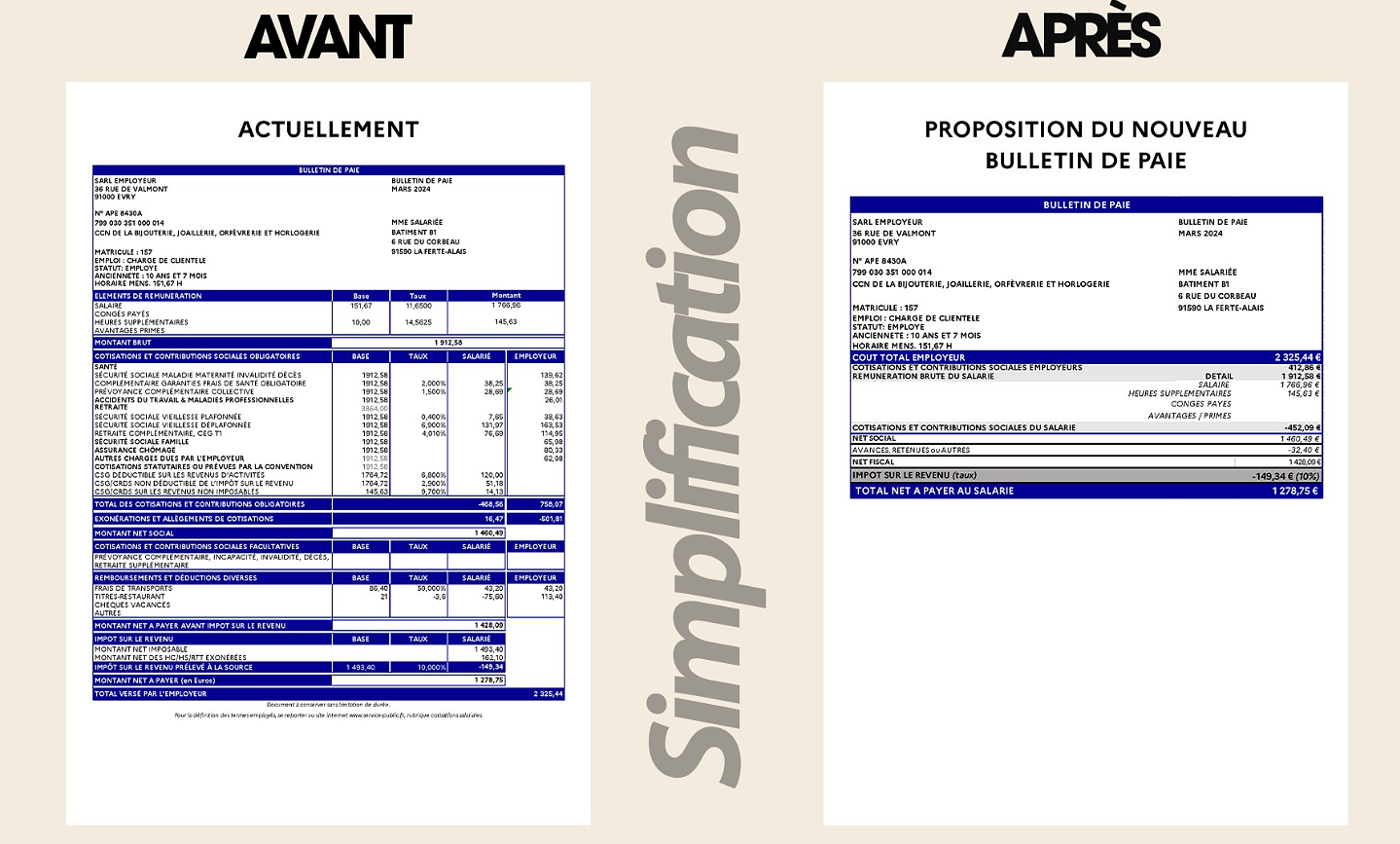

“I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing “I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy

“I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy 25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits

25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan

At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga

Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker

Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League

Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops

OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet

Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid

Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid