“My head is divided into three,” says Ema Simurda. "There's me, Ema, private and there's Good Bank and Farmie." She laces her fingers together on the closed MacBook in front of her, smiles a relaxed lipstick smile, and exudes clarity. The 34-year-old asserts that it is not difficult for her to keep her head despite the division into three. And an overview of their start-ups.

Yes, they would have been warned that you could get bogged down with too many projects. But she sees no danger there: "I'm a total jack of all trades. A pathology that I share with many founders. And if that wasn't good for me, then I would do something else."

This is how someone speaks who has already had a few founding years behind her. which has undergone maturation. And maybe a crisis too.

Ema Simurda was born in Osijek, an inland Croatian city near the borders of Hungary and Serbia. That's a long way from the "oh so beautiful Croatia" people used to rave about, she laughs. "I'm at the Croatian sea myself once every 15 years."

When she was four years old, war broke out in her homeland and she fled to Graz with her mother, grandmother and aunt. There she manages to go to high school, but drops out at the age of 15. "I can't deal with authorities," she says today. "School just depressed me."

She always knew that she would want to work independently. And she starts as a teenager by taking her A-levels on her own without going to school. Five years of teaching alone and only from books - that was hard. Incredibly hard, she says. But she had one goal in mind that she should achieve: she was admitted to study at the Vienna University of Economics and Business.

In the years before and after her studies, she tried out different areas: she worked as a model. Did freelance PR and marketing. Became the mother of a daughter at a young age, moved to Berlin. There she started in business development at Hubject, an electromobility joint venture between Daimler, BMW and Bosch, among others.

At first she thought she had arrived in this area. "My father was a total car nerd," she explains her enthusiasm for e-mobility. But then she got to know an even more fascinating area: Mobility has always been about the question of what the cities of the future will look like. And vertical farming always played a major role in them.

In 2017, Ema Simurda founded Good Bank together with Leandro Vergani, which she says is "Germany's first vertical farm-to-table restaurant". “I felt that vertical farming technology was known to people but never grasped. Vertical farming happened somewhere out there where nobody sees it,” she says.

"We therefore wanted to implement a very accessible restaurant concept in order to make vertical farming a direct experience - for everyone."

The first shop in the middle of Berlin-Mitte, between Rosenthalerplatz and Alexanderplatz, was a huge hit in the media, Simurda recalls: "The initial phase was crazy." Photographers and TV crews took turns and reported on the brightly colored shop with the glowing pink Infarm grow cabinets growing two varieties of lettuce and baby kale, which were made into salads and bowls at the counter in front.

The Berlin VC Atlantic Foodlabs invested right from the start, in 2019 Simurda made another round of financing, in which Christophe Maires Fund again invested together with Döhler Ventures and DMK Deutsches Milchkontor.

Simurda and Vergani started planning the second branch, thought about a restaurant chain, started catering, reached new target groups beyond the Berlin-Mitte bubble and found out: The concept of the fresh dishes, which end up in the bowl directly from the greenhouse, went up there too. The signs pointed to success - and then came Corona.

As a catering entrepreneur, the pandemic hits Simurda extra hard - one would think. In fact, the smile on the founder's face remains genuine and relaxed when she reports from March 2020: "Until then, our company's history had been one wild ride. I honestly haven't had two days in a row that I haven't worked," she says.

Then the first lockdown forced her not to work: "When everything was cleaned up and our three restaurants were closed, I went home and slept for four days." And then the founder began to take advantage of the downtime - and not, to adapt the business model as quickly as possible, to quickly stomp delivery formats out of the ground like other restaurateurs, no. "I used the time to lose the tunnel vision and ask: Is this what we really want?"

Can Good Bank really promote the idea of vertical farming with a restaurant chain and catering? Does it reach enough people this way? How could that be possible with less heavy operations? "That was really good," says Simurda in retrospect.

“I have always been able to see opportunities in crises. My mother had fled the war. Maybe that's where it comes from," says the founder. "When I sit in a burning room, a thousand ideas, strategies and solutions come to me. I need that pressure.”

The trick, of course, the founder thinks, would be to be able to create this pressure artificially in the head. To put oneself emotionally so convincingly in a worst-case scenario that the solution automatism is triggered. Maybe that could be exciting coaching that she could give, Simurda thinks with a laugh. "Or I'll write a book about it - when I've figured out how to consciously put yourself in crisis mode without a real threat of an existential crisis."

Ultimately, this resulted in several successful additional pillars for Good Bank. The founder reports that it was relatively easy to grow a cooking box business from the catering business. "It gave us a small foothold in e-commerce," she says. But Hello Fresh never wanted to attack her with it. Simurda also contacted Edeka and brought fresh bowls of lettuce and green vegetables from the Vertical Farm to food retailers. "If we had stiffened, also in our heads, it would have been bad."

And a third idea came up as part of Ema Simurda's Corona Pivot: She decided to produce vertical farms herself. Hardware - but "lean and bootstrapped". To do this, she founded her own new company in 2021: Farmie. The time was ideal: At the latest since the outbreak of war in Ukraine, everyone has become more aware that we have to produce in a more resource-efficient manner, including in the food sector.

And that freshness cannot always be guaranteed, that some products simply cannot be delivered. In addition, customers and real estate partners have been asking her for a long time whether she could set up such chic grow cabinets as the ones in the Good Bank Restaurant. To date, the Berlin Unicorn had been Infarm.

When Simurda starts designing her own cabinets, one thing is important to her: it has to be a plug-and-play model. “The hardware should be as basic as possible and as complicated as necessary so that whoever uses it has fun with it. That makes the difference,” she is convinced.

For other cabinets, you need supply and waste water lines, a separate circuit and you have to book the regular service when you buy it. All of that is different with Farmie. The 2.65 meter high cabinets are on castors and are therefore completely flexible, all you need is a normal socket within easy reach.

Water is filled into a tank in the lower part of the cabinet. Restaurants, cafés, canteens or hotels that have the space for one or more of the quite sizeable cupboards could harvest 250 to 750 of their own lettuce a month, depending on the variety.

That equates to several hundred kilos a year. 32 Farmie cabinets are now in use. And a mushroom farm, a test balloon. The second, completely revised version of the farms is scheduled to go on sale before the end of this year.

She works at Farmie without the support of investors, says Simurda. It works because they only make to order. She works with freelancers for architecture and product design, and with several small and medium-sized companies for production.

“It may sound banal now, but: in the end it is a vegetable garden that is technologically supported. I find it exaggerated to sell something like this as rocket science.” It is important that Farmie causes little energy costs and that a typical customer such as a restaurateur can quickly instruct a part-time employee in how to use it.

And then she offers her customers this: seedlings and seeds "as a service". Simurda has hired a scientist who deals with "biofortification", i.e. who ensures that the nutrient content of certain types of lettuce is optimized to a maximum, for example by selectively crossing certain types of lettuce. Controlling the light or certain nutrient solutions used to water the seedlings could also improve the taste and quality of the vegetables, she says.

All this and more goes through the tripartite head. Finally, she reveals the secret of why she doesn't burst: "I can adapt very quickly so that stressful situations affect me less emotionally."

"Everything on shares" is the daily stock exchange shot from the WELT business editorial team. Every morning from 7 a.m. with the financial journalists from WELT. For stock market experts and beginners. Subscribe to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcast, Amazon Music and Deezer. Or directly via RSS feed.

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction

His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial?

Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial? What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain?

What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain? Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50

Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50 H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States

H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation

Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application

Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application “I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing

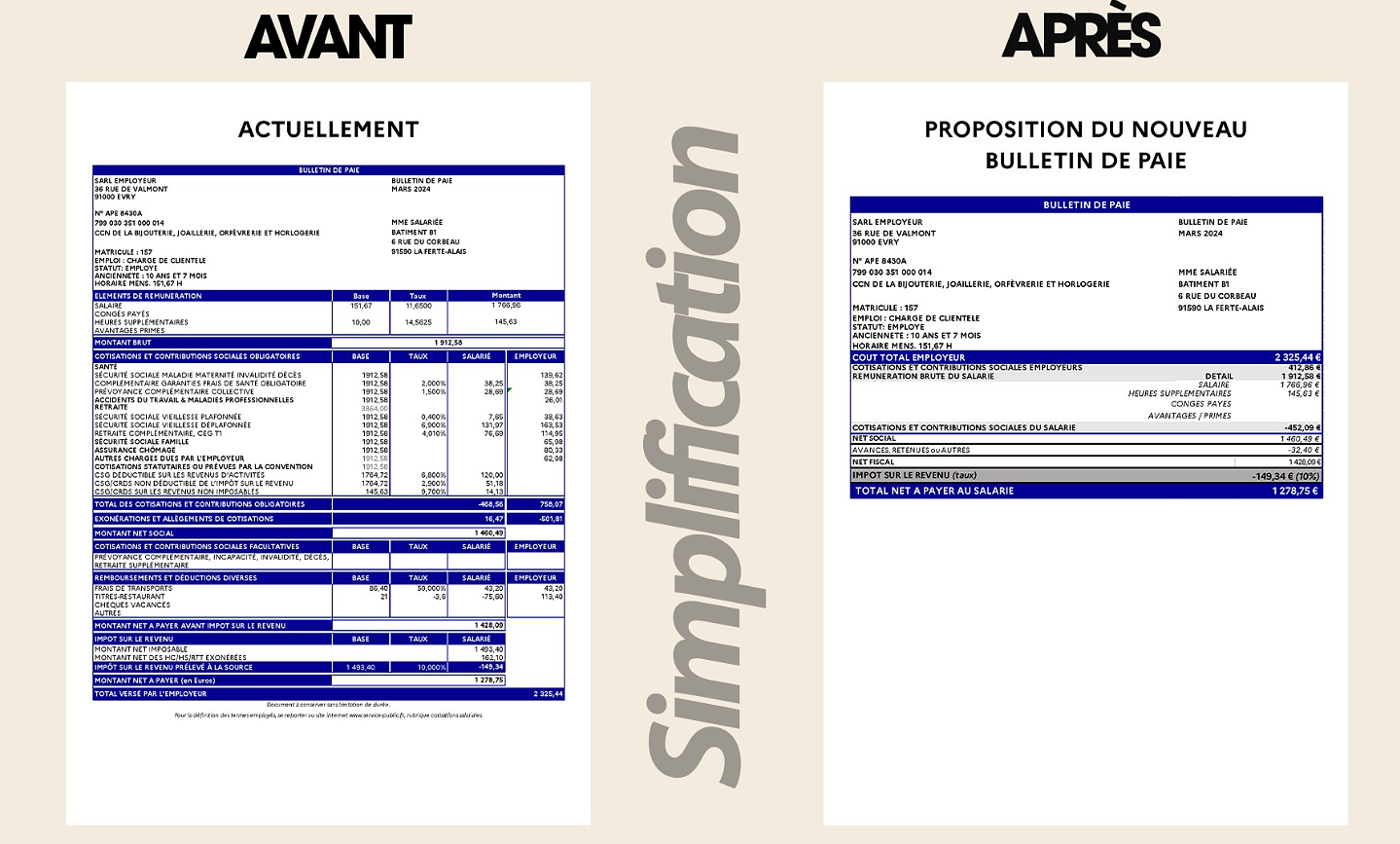

“I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing “I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy

“I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy 25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits

25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan

At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga

Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker

Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League

Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops

OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet

Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid

Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid