The phase of galloping food prices last summer and autumn seems to be over. In the meantime, bread, butter and meat have tended to act as a brake on prices in an environment that continues to be characterized by massive inflation. The calming down in food is reflected "in the shopping basket, with a direct price dampening effect," commented Friedrich Heinemann, department head at the ZEW Institute, on the latest inflation figures. The trend will probably continue for the time being: "In the coming months, the inflation rate in Germany and in the euro zone will fall even more significantly."

The Mannheim economist is not alone in his confidence. Many of his colleagues see it the same way. However, a great unknown hovers like a ghost over all the forecasts and calculations: will the hostile countries Russia and Ukraine stamp out their agreement on grain exports, or can they come to an agreement again? The decision must be made soon - the current regulation expires in March.

If the contract topples, there is a risk that the scenario from early summer 2022 will be repeated. Immediately after the outbreak of the Ukraine war in February, for example, the price of a tonne of wheat on the Matif futures exchange in Paris shot up from around 250 to over 420 euros. In mid-May, it reached a record high of EUR 438.25 per ton, driven by the war between two of the world's most important grain exporting countries.

The consequences were far reaching. Agricultural goods are all globally traded commodities. And not only grain is affected by the conflict. With its huge arable land, Russia is also one of the world's most important suppliers of fertilizers, animal feed and other agricultural raw materials.

The wave of inflation also affected a wide range of products. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) also determined historic highs for sugar, meat and vegetable oil for 2022 as a whole. All in all, their food index jumped a whopping 14 percent over the previous year.

The grain agreement brokered by the United Nations (UN) and Turkey calmed things down from early summer. In January 2023, for example, the FAO index for staple foods fell for the tenth time in a row according to their latest monthly report. Measured against the peak reached in March 2022, the decline adds up to almost 18 percent. On the Matif futures exchange, a ton of wheat is now trading for well under 300 euros again. Equipment is also getting cheaper. "The fertilizer prices are falling like a stone," reported the specialist portal "Agrarheute" these days. The last time farmers could have bought something so cheap was two years ago.

The drop in grain prices is helping to stabilize the food situation in many countries in North Africa, which is largely dependent on supplies from Russia and Ukraine. The trend reversal has also arrived in Germany and Europe. "The easing of food prices in wholesale is also likely to have an impact on consumer price inflation," expects Sebastian Dullien, head of the Institute for Macroeconomics and Business Cycle Research (IMK).

For a long time now, food prices in Germany have only seemed to know one direction: upwards. But suddenly there is a bit of hope for a change in trend - from the refrigerated section. Butter prices began to slide across the board.

Source: WORLD

Consumers can already see from many price tags in stores how thoroughly the panic on the food markets has subsided. Take butter, for example: Since the beginning of February, a number of discounters in Germany have only been charging 1.59 euros for the 250 gram pack of their respective house brand, even beyond promotional goods. Previously, it was usually EUR 1.99, and at the peak of the inflation wave in the summer, around EUR 2.30 was asked for and paid for. Discounters and supermarkets have also lowered their prices for other so-called key products, including coffee, whose prices consumers pay particular attention to.

The initiators of the grain agreement in particular are celebrating its impact. At a press conference, the Turkish Rear Admiral Selçuk Akarı spoke of a “resounding and unprecedented success”. But the euphoria could soon turn into the opposite. The calm on the markets may prove to be deceptive - if negotiations to extend the agreement fail. The markets had already reacted very nervously in mid-October, when their term was extended by 120 days for the first time.

The poker for the new round has long since begun. Sergey Vershinin, Russia's deputy foreign minister, recently made an extension of the agreement dependent on the lifting of export restrictions on Russian agricultural products. Kiev, in turn, demands that only larger ships may be used to export grain and vegetable oil within the framework of the agreement.

Background: The Ukrainians accuse the Russians of being deliberately hesitant about the controls provided for under the agreement in order to hinder Ukrainian exports. The checks carried out jointly with Turkish and UN inspectors are intended to prevent the illegal transport of people or goods such as war equipment. Russia denies a deliberate idleness tactic. But the numbers speak a different language. According to the UN, the number of Ukrainian ships cleared for passage through the Bosphorus Strait fell to an average of 2.5 per day in January, the lowest level since August.

As recently as December 2022, 3.4 freighters were being handled per day, and as many as four to five in midsummer last year. The consequences are obvious. According to data from market observer Lloyd's List, Ukraine's grain exports fell by 19 percent in a month in January.

The grain agreement is still stabilizing markets worldwide. Failure would hit them in a situation that, beyond the armed conflict in Eastern Europe, has become increasingly fragile in recent years due to a bundle of stress factors. Poor weather conditions in important producer countries, for example, resulted in some disappointing harvest volumes, while major customers stocked up under the impact of the corona pandemic and thus boosted demand. World Bank expert John Baffes compares the current market situation with a twin-engine aircraft with only one propeller working: “As long as this engine works, everything is ok. If he fails, you have a problem," he told the Financial Times.

Shrinking grain stocks, for example, are having a destabilizing effect. According to the US Department of Agriculture, they had still reached a comfortable level of 636 million tons at the end of the 2019/2020 marketing year, according to the Americans, at the end of June last year there were just 591 million tons stored in silos worldwide - the lowest level in six years . Experts had actually expected increasing inventories.

According to new FAO figures, the global wheat harvest reached a new high of 794 million tons last year. However, not only in Ukraine, but also in the USA and the EU, the quantities were lower than predicted. In the comparatively dry summer of 2022 in Germany, the combine harvesters brought in around 43 million tons of grain. This is slightly more than in the previous year, but less than the long-term average. However, larger harvest volumes in parts of South America as well as in Canada and Russia were able to make up for the gaps.

However, looking at the harvest yields an incomplete picture. The best indicator of the future stability of grain prices is the relationship between supply and demand, the so-called “stock-to-use ratio”. In this way, market participants calculate how long stocks would last to cover world demand.

The results are not very encouraging. By the end of June this year, the Washington-based Research Institute for International Food Policy (IFPRI) is forecasting that supplies will probably last just 58 days of consumption. In mid-2021, the value was just under 69 days. The analysts see one of the main reasons for the negative trend in the Ukraine. The producers in the country, which otherwise supplies almost nine percent of global exports, sowed around 40 percent less wheat than usual last autumn because of the armed conflict. A slump in earnings is thus preordained for the current year.

If the forecast comes true, the key figure would soon be at its lowest level for 15 years. "It can be assumed that the instability of prices will increase with every major drop in supply," warn the IFPRI experts. The effect will be all the more intense the longer Ukraine's ability to export remains restricted. Consumers around the world could feel this.

"Everything on shares" is the daily stock exchange shot from the WELT business editorial team. Every morning from 5 a.m. with the financial journalists from WELT. For stock market experts and beginners. Subscribe to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcast, Amazon Music and Deezer. Or directly via RSS feed.

Sydney: Assyrian bishop stabbed, conservative TikToker outspoken on Islam

Sydney: Assyrian bishop stabbed, conservative TikToker outspoken on Islam Torrential rains in Dubai: “The event is so intense that we cannot find analogues in our databases”

Torrential rains in Dubai: “The event is so intense that we cannot find analogues in our databases” Rishi Sunak wants a tobacco-free UK

Rishi Sunak wants a tobacco-free UK In Africa, the number of millionaires will boom over the next ten years

In Africa, the number of millionaires will boom over the next ten years WHO concerned about spread of H5N1 avian flu to new species, including humans

WHO concerned about spread of H5N1 avian flu to new species, including humans New generation mosquito nets prove much more effective against malaria

New generation mosquito nets prove much more effective against malaria Covid-19: everything you need to know about the new vaccination campaign which is starting

Covid-19: everything you need to know about the new vaccination campaign which is starting The best laptops of the moment boast artificial intelligence

The best laptops of the moment boast artificial intelligence Bitcoin halving: what will the planned reduction in emissions from the queen of cryptos change?

Bitcoin halving: what will the planned reduction in emissions from the queen of cryptos change? The Flink home shopping delivery platform will be liquidated in France

The Flink home shopping delivery platform will be liquidated in France Bercy threatens to veto the sale of Biogaran (Servier) to an Indian industrialist

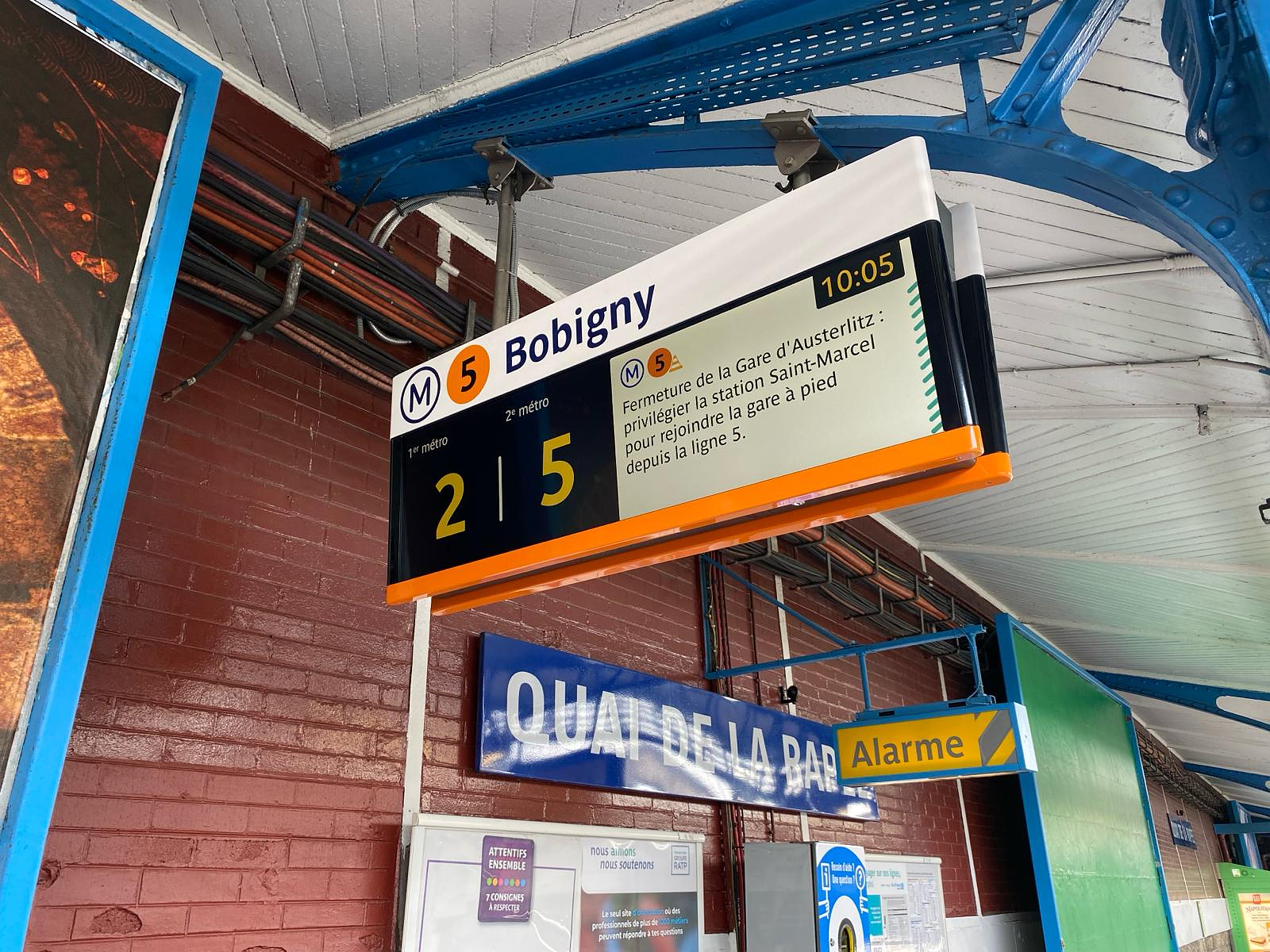

Bercy threatens to veto the sale of Biogaran (Servier) to an Indian industrialist Switch or signaling breakdown, operating incident or catenaries... Do you speak the language of RATP and SNCF?

Switch or signaling breakdown, operating incident or catenaries... Do you speak the language of RATP and SNCF? The main facade of the old Copenhagen Stock Exchange collapsed, two days after the fire started

The main facade of the old Copenhagen Stock Exchange collapsed, two days after the fire started Alain Delon decorated by Ukraine for his support in the conflict against Russia

Alain Delon decorated by Ukraine for his support in the conflict against Russia Who’s Who launches the first edition of its literary prize

Who’s Who launches the first edition of its literary prize Sylvain Amic appointed to the Musée d’Orsay to replace Christophe Leribault

Sylvain Amic appointed to the Musée d’Orsay to replace Christophe Leribault Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy

Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy During the night of the economy, the right points out the budgetary flaws of the macronie

During the night of the economy, the right points out the budgetary flaws of the macronie These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Europa Conference League: the semi-final flies to Lille, which loses to the wire against Aston Villa

Europa Conference League: the semi-final flies to Lille, which loses to the wire against Aston Villa Lille-Aston Villa: Cash disgusts Lille, the arbitration too... The tops and the flops

Lille-Aston Villa: Cash disgusts Lille, the arbitration too... The tops and the flops Handball: Les Bleues in the same group as Spain at Euro 2024

Handball: Les Bleues in the same group as Spain at Euro 2024 Europa Conference League: for Létang, Martinez “does not have the attitude of a high-level athlete”

Europa Conference League: for Létang, Martinez “does not have the attitude of a high-level athlete”