Anyone who is on Instagram, YouTube, Facebook or TikTok often comes across offers that sound tempting: from weight loss powder to lucrative investments. In our series, reporter Judith Henke takes a look at these products. What is behind it, how serious are you?

***

One of my favorite things to do on Instagram is to guess what ads I'll see as I scroll through the app.

Sometimes Instagram seems to know me well – almost a little too well: How does the app know what brand my car is, for example? But sometimes the products that are advertised in the ads completely ignore my needs.

An example of this is an ad that tries to grab my attention with the following promise: “No diets, no bans – and still lose weight? Decode how your metabolism works with a DNA test and discover the natural way to permanently lose weight.”

Aside from the fact that I have absolutely no intention of starting a diet, I can't think of anything more awkward than sending my DNA sample to a total stranger. What if my DNA is not only used for metabolic analysis?

However, since this advertising will be displayed to me more and more frequently and intrusively in the coming weeks - often garnished with some sort of discount campaign that I shouldn't miss - my journalistic curiosity was aroused. So I go to the Lykon manufacturer's website.

There I am asked what my goal is: “lose weight”, “digestion” or “longevity”. I just click on “lose weight” and am forwarded to a kind of questionnaire. Lykon wants to know how I feel today, how much I weigh, how tall I am, what gender I am, whether I like meat or not, how much fruit, vegetables and sweets I eat, how active I am in my free time and if I'm just sitting around at work.

Pretty personal. After I've answered all the questions, Lykon suggests a few products to me - including the myDNA Slim Text for a mere 189 euros. I order that. A few days later the test is in my mail.

The package includes a cotton swab with a tube. With the cotton swab, I now take a swab on the inside of my cheeks, then I put it in the tube.

But the tube doesn't have my name written on it - instead I'm supposed to put a sticker on it with a barcode printed on it.

I don't write my name on a piece of paper that I'm supposed to send, but put two stickers on it, one with a barcode and one with an ID number. This ID is assigned to my customer account. I also have to enter them in the manufacturer's smartphone app in order to be able to view my test results there later.

Now it takes about three weeks until I get my result. Then the time has come: A more than 60-page analysis of my metabolism is there.

According to the summary, it is one thing above all: completely average. I have a normal feeling of hunger, a normal tendency to be overweight and a yo-yo effect and should focus on a mixture of strength and endurance sports.

What's a little more interesting: According to the test, I'm a carbohydrate type. Accordingly, the consumption of large amounts of carbohydrates has little effect on my weight, but a high-fat and protein-rich diet does. Does that mean I can't eat eggs anymore and instead have to cook potatoes every day?

Not quite: A page down the page says normal amounts of protein wouldn't be stored as body fat for me.

Also, on a list of foods I should eat often, sometimes, or not at all, eggs are listed under the “2-3 servings per week” category. On the other hand, I should avoid sweets – I read that shortly after I ate my three Nutella toasts for breakfast.

A breakfast routine I've had for a good three years. However, I did not gain weight as a result, despite the allegedly poor fat metabolism according to the test. That's probably because I exercise four times a week - of course, that can't be read from my DNA. So is the myDNA Slim test particularly meaningful at all?

I ask Julia Sausmikat, a nutritionist from the North Rhine-Westphalia Consumer Advice Center. She's skeptical. The manufacturer states that a combination of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) was analyzed for the text.

These would each affect a specific gene. According to Sausmikat, these SNPs are indeed associated with metabolic effects. But: “They only account for around six percent of the BMI variance. So only a small part of the weight is affected by genetic changes.”

But what exactly are these SNPs? I let Christian Schaaf, who heads the Institute for Human Genetics at Heidelberg University Hospital, explain it to me step by step. According to him, the characteristics of a person are determined by the genetic material, also called the genome.

Genetic information is stored on DNA in the form of chromosomes. There are a total of 23 pairs of chromosomes in the human body cells.

In the germ cells - which are passed on during reproduction - it is just a single set of chromosomes, i.e. 23 chromosomes. These contain about three billion base pairs.

A gene is a specific sequence of these base pairs. It is responsible for making RNA and in many cases is translated into proteins. In total, a genome has more than 20,000 of these protein-coding genes. In addition, there is about the same number of non-protein-coding genes.

"Even though everyone has the same genes, they are still genetically unique," says Schaaf. This is due to the different variations of the base pairs - and these are called single nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs for short. "Every single person has four to five million of them," says the human geneticist.

According to Lykon, he examined 23 of these SNPs in 19 genes – that is, only a fraction. "The significance of this analysis is therefore very low," concludes Schaaf.

So did I spend almost 200 euros for nothing? I contact the manufacturer directly. Lykon's head of communications, Julia Teuber, answers me. She initially contradicts the consumer advocate's objection: there are indeed many studies showing the influence of SNPs on metabolism. "The overall influence of the interaction of the various SNPs is between 40 and 60 percent in the studies," she emphasizes. In addition, when it comes to losing weight, personalized approaches are more sustainable than those that ignore genes.

She also responds to the criticism of the human geneticist Christian Schaaf. With the myDNA Slim test, Lykon has so far concentrated on 23 SNPs, "which are particularly meaningful for the individual metabolism of nutrients." Some of the competition's tests only focus on four SNPs. Lykon is also currently converting the myDNA Slim test to 46 SNPs. The new test would be officially launched on Monday, she says.

In the more than 60-page analysis, all genes in which SNPs were examined are listed, in chapter eight of the report my laboratory results are explained in more detail. For example, the FTO gene was analyzed.

This certainly has characteristics for which a higher risk of weight gain has been reported in the scientific literature, as Reiner Siebert, head of the Institute for Human Genetics at the University Hospital Ulm, and his deputy Ole Ammerpohl explain to me. But: "The effects that certain variations have on the weight are between one and three kilograms."

The two human geneticists to whom I sent my test report cannot determine exactly how Lykon proceeded with the analysis. This is due to the somewhat vague formulations of the manufacturer.

For example, there is talk of examining a SNP of the ACTN3 gene. But which one – the reader does not recognize that, at least at first glance. Lykon communications chief Teubert argues that this information would overload the report and reduce its readability.

Also puzzling: Depending on the genetic variation analyzed, something else is recommended to me. As a result, the report contradicts itself in some places, for example I am suggested to do more endurance sports, at other times I am encouraged to do weight training.

Sometimes I don't have a tendency to the yo-yo effect, sometimes I do. Depending on my genotype, I burn fat well or badly. A journalist who tested the product for Der Spiegel also encountered these contradictions.

Why is that? Lykon spokeswoman Teubert replies that the SNPs differ in the degree of their effect on metabolism. "What is important, however, is the interaction of the genes and consequently the overall result of the analysis," she emphasizes. Lykon calculates the individual typing results in a self-developed algorithm. But I don't know how this algorithm does it.

But no matter how the algorithm is structured and how many SNPs were examined - the current state of research is not far enough to fully analyze the influence of DNA on metabolism, as human geneticist Christian Schaaf explains

"For this purpose, for example, a test and a control group of hundreds of thousands of people would have to be analyzed with regard to their entire genetic code and observed over the years, both in terms of weight and lifestyle," he says. The data situation is therefore not yet comprehensive enough.

Keyword “data”: What actually happens to the information about my DNA after Lykon has evaluated it? When I registered, I had to agree to the following procedure: My data will be passed on to a cooperating laboratory in pseudonymised form for the purpose of evaluation.

In addition, Lykon would statistically evaluate data for "quality assurance purposes", but only pseudonymised raw data would be used here.

Under the data protection notices I also find the information that public bodies and institutions such as law enforcement agencies should theoretically be able to access my data.

However, Lykon communications manager Teubert emphasizes that Lykon does not pass on any sensitive data to third parties. However, to be on the safe side, I request that Lykon delete all my data.

In doing so, I refer to the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). I got the tip from Thilo Weichert from the German Association for Data Protection.

He warns against sending DNA samples to a complete stranger just because you want to lose weight. Because there is no characteristic of a human being that is more personal and unique than DNA. It should therefore not fall into the wrong hands under any circumstances - for example because data from a private provider has been hacked.

"Huge numbers of companies are interested in DNA data and willing to pay big bucks for it," he explains. So Lykon is sitting on a gold mine. For example, insurers would be interested in the DNA of their customers because they could identify health risks from this data - and charge corresponding premiums.

According to the Genetic Diagnostics Act, which regulates the requirements for genetic tests and the use of the samples, insurers can require potential customers to present genetic tests that have already been carried out before taking out insurance that covers sums of more than 300,000 euros in a one-off payment or 30,000 annuities.

Because some insurance companies check the health of their customers before signing the contract. For example, if you want to take out disability insurance, you have to fill out a long questionnaire in which you have to provide information about previous illnesses or dangerous hobbies.

Insurers rule out certain health conditions – including rheumatism, severe forms of obesity and mental illnesses – or demand high risk premiums on the premium.

But concealing previous illnesses is of no use to the consumer - because the insurer usually asks for the medical records of the last ten years for comparison when a BU pension is applied for.

If the insurer then encounters contradictions, he can refuse to pay out the BU pension – and the insured has paid in for years in vain. This also applies if he accidentally provided incomplete information - i.e. simply forgot the genetic test.

Does that mean that before I do a DNA weight loss test, I should take out disability insurance as soon as possible - at least if I want to arrange a BU pension of 2,500 euros a month?

Lykon spokeswoman Julia Teubert can reassure me a bit here: Lykon is exempt from the Genetic Diagnostics Act, which allows insurers to require customers to submit genetic test results for large sums. The reason: Lykon's tests are lifestyle products, since they provide information about the metabolism and sport type, but not about existing diseases.

What luck - not only for me, but especially for Lykon: Due to this legal gray area, the manufacturer is also exempt from the doctor's reservation, which is anchored in the Genetic Diagnostics Act.

Only a doctor should have carried out a medical genetic test. And he should have enlightened me in much more detail than the manufacturer Lykon, behind whose terms of use I just had to quickly tick a box.

It doesn't matter whether it's lucrative investments, dental splints or coaching offers: anyone who uses social media is overwhelmed with product recommendations. What's behind it? How serous are they? You can find out in our podcast "Die Netzcheckerin". Subscribe to Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Deezer, Amazon Music or directly via RSS feed.

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction

His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial?

Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial? What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain?

What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain? Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50

Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50 H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States

H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation

Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application

Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application “I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing

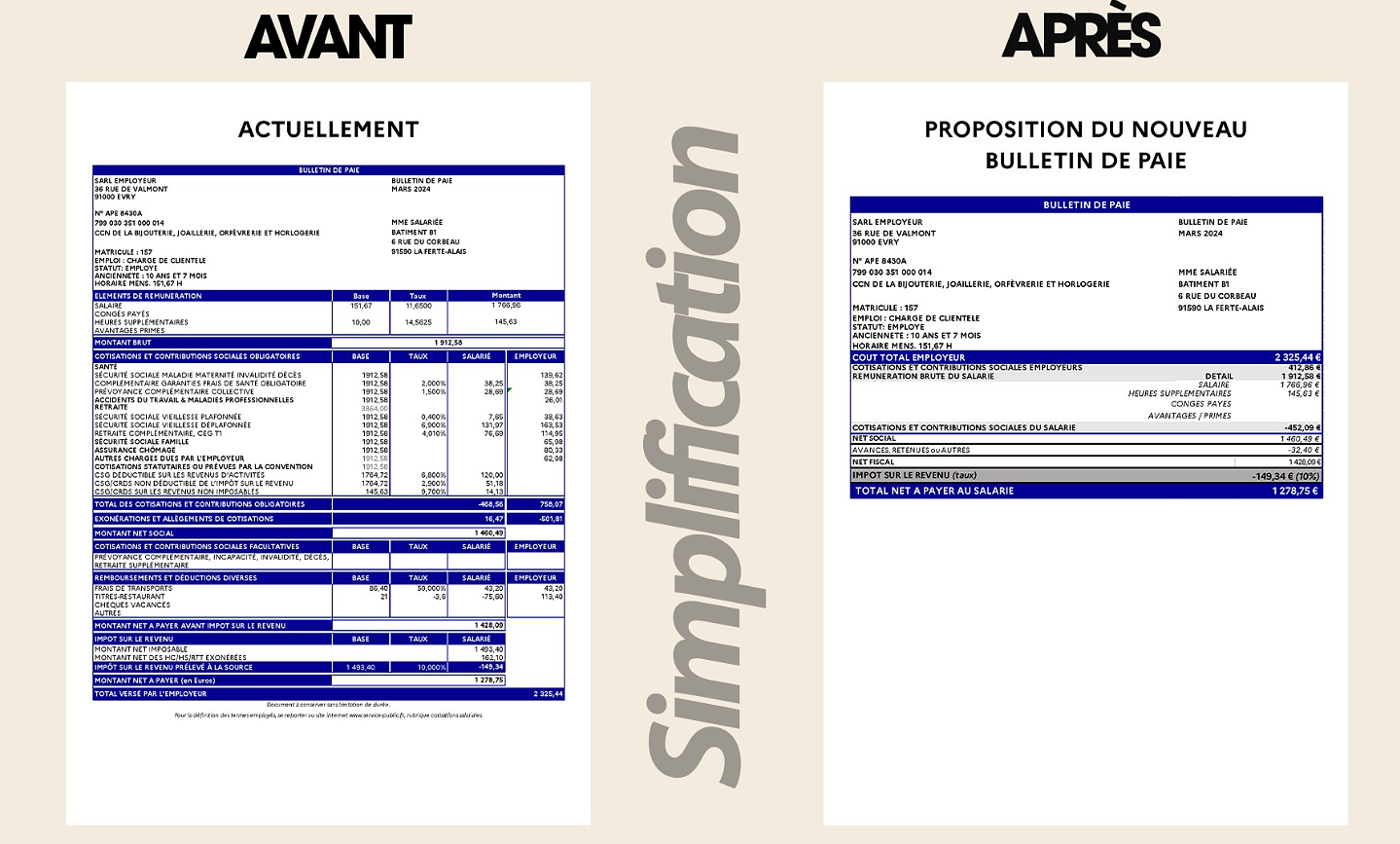

“I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing “I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy

“I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy 25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits

25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan

At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga

Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker

Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League

Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops

OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet

Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid

Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid