No, these three didn't just want to do politics - they wanted to fulfill a mission. Katja Dörner in Bonn, Sibylle Keupen in Aachen and Uwe Schneidewind in Wuppertal left no doubt about that when they won the local elections two years ago. When observers nationwide diagnosed a "green wave from the West". And when the three rose to become the first green mayors of NRW. Right from the start they talked about the "big transformation project" (Schneidewind), about "the joint mission to transform our cities" (Keupen) - about the vision of creating a climate-neutral city with green mobility in a hurry. Now the question arises: what did the three of them achieve - especially in the area of the traffic turnaround, which is so controversial but so important for the transformation?

The balance is different - which has to do with the staff. An experienced politician governs in Bonn. Katja Dörner has been in politics for 20 years, she sat in the Bundestag for eleven years and as deputy leader for seven years. She purposefully built the coalition in the city council with which she could embark on the path of ecological transformation most resolutely - a left-wing alliance with the SPD, Lefter and Volt. Of the three Greens, she pushed through the most far-reaching reforms to date. Uwe Schneidewind, on the other hand, longtime head of the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy, was a political novice in 2020. He was elected as a candidate by the Greens and the CDU, but soon slid into a row with the city's CDU grandees. The coalition broke up. This week, an alliance of CDU, SPD and FDP confirmed that it would steer the fate of the city in the future. The CDU complains that Schneidewind misjudges the balance of power. And Wuppertal's FDP district chairman Marcel Hafke says that Schneidewind finds it "difficult to organize majorities and find the necessary ability to compromise. Unfortunately, one notices that he has not learned the political craft". In Wuppertal, the green turnaround in traffic was, unsurprisingly, meager.

Similar in Aachen: Sibylle Keupen was a theater teacher before she, inexperienced like Schneidewind, was proposed by the Greens as head of the town hall. She also failed to build a coalition with the CDU - which, according to Aachen's CDU parliamentary group leader Iris Lürken, was by no means just due to differences of opinion, but also to the "sometimes difficult to bear way with which Ms. Keupen tackles factual issues. Every detailed decision about a bollard on a street corner" is "highly morally charged and declared to be without alternative due to climate change". Rejected by the CDU, Keupen tried changing majorities before she managed to form an alliance with the SPD. That was sealed this week. Nevertheless, the SPD continues to criticize Keupen sharply. And complains that you lack experience in personal dealings as well as in political shaping. Keupen's previous attempts at transformation therefore seem rather modest. A turn towards the traffic of the future can be observed most likely in Bonn. Without hesitation, Katja Dörner took a lane away from car drivers on central traffic axes and reserved it for buses and cyclists (so-called environmental lanes).

Parking fees were sometimes quadrupled, sometimes twelvefold. She is also working on an "enlarged car-free zone", a part of the city is already no longer accessible by car. Single-lane roads lined with speed cameras, mostly with a speed of 30 km/h, will soon remain the axes of car traffic, which corresponds to Dörner's goal of reducing through traffic. “The residents are certainly happy about that, but many commuters or visitors are desperate when they are stuck in traffic jams, are allowed to drive at a maximum of 30 km/h even at night or have to look for alternative routes through Bonn’s rural structures,” complains Bonn’s CDU parliamentary group leader Guido Déus.

In Aachen, on the other hand, not much has changed since 2020 in terms of the 30 km/h limit, parking prices or environmental lanes. Also, fewer roads than in Bonn were closed to cars. But where this happened, Keupen relied on the bollard as an instrument. Their fondness for the red and white poles is so pronounced that it's been called "polleritis" citywide. The bollards have one major advantage: the car-free zones marked in this way can quickly be reopened to cars, for example for suppliers, on special occasions or in emergencies. That seems to be catching on. Other cities also showed interest in Aachen's bollard course.

In Wuppertal, too, the pace of reform is rather slow - if only because the partners lack the cutting edge for a faster pace. But he had also started with the intention of shaping the traffic turnaround by consensus. If Schneidewind considers blocking a street for cars, he first starts extensive citizen surveys and public debates. He is also looking for the backing of the district councils. The price of this consensus-oriented approach: so far he has only converted 85 meters of street into a car-free zone - which he himself declared to be "manageable". Even FDP boss Hafke calls for "more courage to get a larger part of the city center car-free and thus a better quality of life".

Bonn's government is also more thirst for action when it comes to bike-friendliness. Cycle paths are emerging everywhere, even on a city motorway. There, cyclists will soon be driving right next to speeding cars. In Aachen, around five kilometers of new cycle paths were also created in the first year. Only Wuppertal lags behind here - but also because cycling in the mountainous city is not so attractive. Here, only one major street has been converted into a bicycle street (cyclists have priority there, cars have to drive at walking speed if necessary).

In Bonn and Aachen, in particular, the construction of cycle paths has also increased the number of construction sites. The citizens of both cities complain about this in surveys and local newspapers. In Aachen there was even a citizens' initiative against it. In both cities, the retail association and IHK warn that the flow of customers and tourists into the city is threatening to shrink, which is also due to transport policy. Which is why Bonn's CDU man Déus believes that the "good goal of the mobility turnaround is being pushed through too ruthlessly by the Greens". Déus, but also retailers in Bonn and Aachen, are calling for alternatives to be created and public transport to be expanded before they ban car traffic. The OBs also try to comply with this. They have increased investments in buses and trains.

But the Greens concede that a municipality can hardly cope with a seamless public transport network, consistently short waiting times, and a hiring offensive for more bus and train drivers. In this respect, the success of their mobility transition depends on the willingness to pay at federal and state level. And it has its limits (see box). Nevertheless, according to polls, the Greens currently have a relative majority in elections in the three cities - although traffic is a major problem for many citizens according to the same polls.

Sydney: Assyrian bishop stabbed, conservative TikToker outspoken on Islam

Sydney: Assyrian bishop stabbed, conservative TikToker outspoken on Islam Torrential rains in Dubai: “The event is so intense that we cannot find analogues in our databases”

Torrential rains in Dubai: “The event is so intense that we cannot find analogues in our databases” Rishi Sunak wants a tobacco-free UK

Rishi Sunak wants a tobacco-free UK In Africa, the number of millionaires will boom over the next ten years

In Africa, the number of millionaires will boom over the next ten years WHO concerned about spread of H5N1 avian flu to new species, including humans

WHO concerned about spread of H5N1 avian flu to new species, including humans New generation mosquito nets prove much more effective against malaria

New generation mosquito nets prove much more effective against malaria Covid-19: everything you need to know about the new vaccination campaign which is starting

Covid-19: everything you need to know about the new vaccination campaign which is starting The best laptops of the moment boast artificial intelligence

The best laptops of the moment boast artificial intelligence Bitcoin halving: what will the planned reduction in emissions from the queen of cryptos change?

Bitcoin halving: what will the planned reduction in emissions from the queen of cryptos change? The Flink home shopping delivery platform will be liquidated in France

The Flink home shopping delivery platform will be liquidated in France Bercy threatens to veto the sale of Biogaran (Servier) to an Indian industrialist

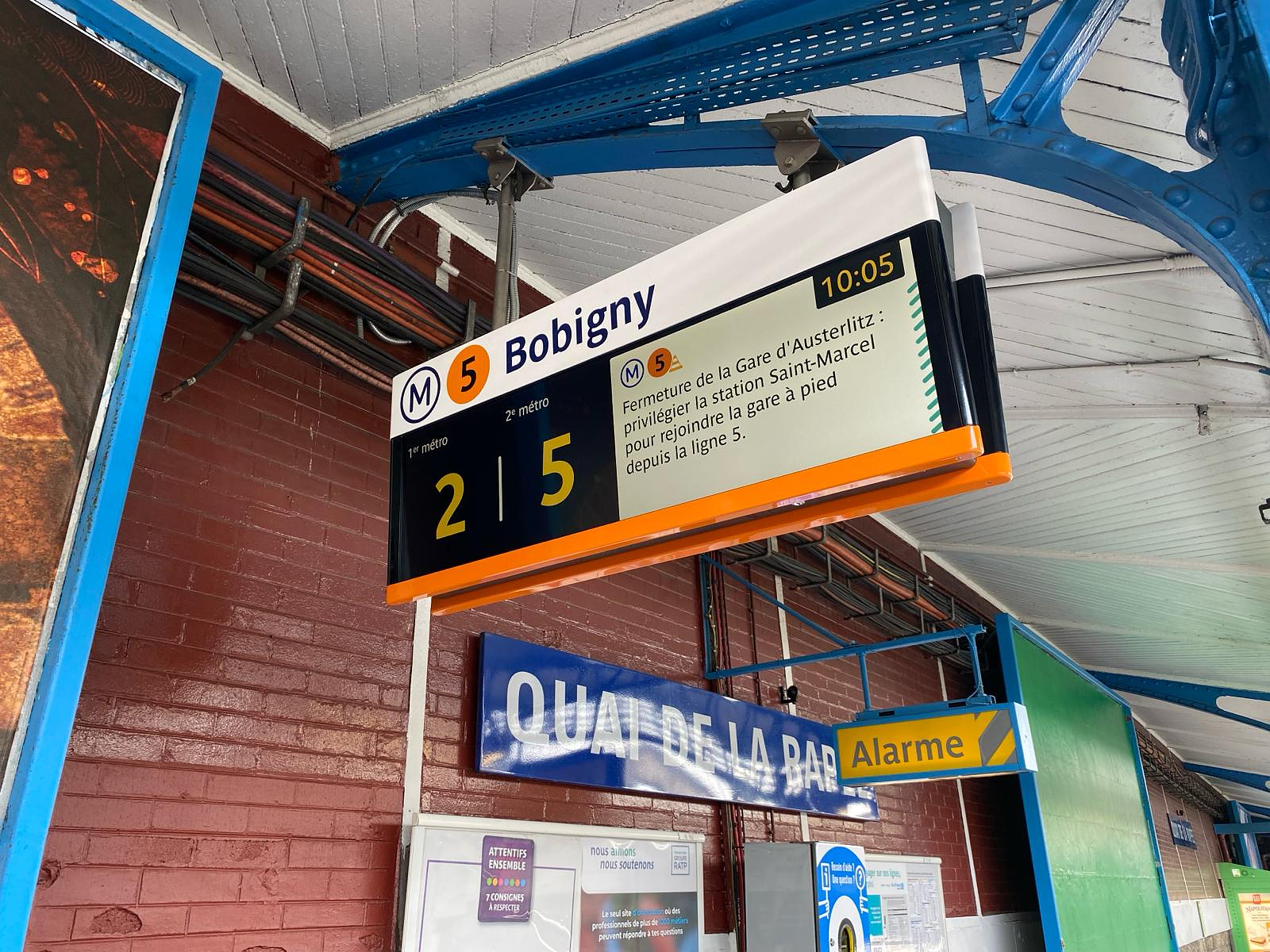

Bercy threatens to veto the sale of Biogaran (Servier) to an Indian industrialist Switch or signaling breakdown, operating incident or catenaries... Do you speak the language of RATP and SNCF?

Switch or signaling breakdown, operating incident or catenaries... Do you speak the language of RATP and SNCF? The main facade of the old Copenhagen Stock Exchange collapsed, two days after the fire started

The main facade of the old Copenhagen Stock Exchange collapsed, two days after the fire started Alain Delon decorated by Ukraine for his support in the conflict against Russia

Alain Delon decorated by Ukraine for his support in the conflict against Russia Who’s Who launches the first edition of its literary prize

Who’s Who launches the first edition of its literary prize Sylvain Amic appointed to the Musée d’Orsay to replace Christophe Leribault

Sylvain Amic appointed to the Musée d’Orsay to replace Christophe Leribault Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy

Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy During the night of the economy, the right points out the budgetary flaws of the macronie

During the night of the economy, the right points out the budgetary flaws of the macronie These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Europa Conference League: the semi-final flies to Lille, which loses to the wire against Aston Villa

Europa Conference League: the semi-final flies to Lille, which loses to the wire against Aston Villa Lille-Aston Villa: Cash disgusts Lille, the arbitration too... The tops and the flops

Lille-Aston Villa: Cash disgusts Lille, the arbitration too... The tops and the flops Handball: Les Bleues in the same group as Spain at Euro 2024

Handball: Les Bleues in the same group as Spain at Euro 2024 Europa Conference League: for Létang, Martinez “does not have the attitude of a high-level athlete”

Europa Conference League: for Létang, Martinez “does not have the attitude of a high-level athlete”