When Bobby Bostic was sentenced at the age of 16 in 1995, the world looked very different: Bill Clinton was US President; Bryan Adams topped the US charts for five weeks with "Have you ever really loved a woman?" and Siemens released the world's first mobile phone that could send and receive text messages.

Bobby Bostic, however, was to serve a 241-year sentence – and die in prison, his judge found in court at the time: "Your regular appointment before the parole board will be in 2201."

Since then, Bostic has spent almost 10,000 nights behind bars in the US state of Missouri, i.e. 27 years. And it could easily have been a lot more if that "miracle" hadn't happened that Bostic keeps telling us about: a change in the law that he himself had fought for for a long time. That's why the 44-year-old was released in November 2022 - and since then has had to get used to the world outside the prison walls, reports the BBC.

Sometimes, as he writes in an article for The Marshall Project, he feels like a newborn. “Many of the places I used to live or hang out in have been demolished or are empty. I've lost count of how many of my peers are dead or incarcerated. The little children I took care of in front of the prison are now bigger than me.” Since his release, he has already been to two funerals.

The people in particular have surprised him since his release, he tells the BBC: "They are so friendly compared to prison. When you go into a grocery store, they say, 'Sir, can I help you?' In prison, all you have is mean faces and bullying.” Outside, however, people smiled at him, little children sometimes waved at him. "This is beauty. That is the joy of being human.”

He also had to relearn many things – some of which his supporters document on Instagram. He finds some things that are taken for granted today strange – such as wireless headphones (“Why are these guys talking to themselves?”), when people speak with loudspeakers (“What is Alexis?”), or automats have sensors (“You wave with your hand and the water comes out?"). He still has to learn how to use a mobile phone or the internet and needs support.

The fact that Bostic was punished so harshly in his teens was due to the judge who was responsible for his case at the time: Evelyn Baker had ruled that the 16-year-old should serve the sentences for all 17 crimes to which he had pleaded guilty, one after the other – and that although he had not seriously injured anyone. She didn't say it, but technically she was sentenced to death, Bostic writes.

Up until then, Bostic hadn't had it easy either. He came from a poor family and grew up in St. Louis practically without a father, but with two siblings. The mother had to make a living on her own and worked a lot. By his own admission, Bostic began drinking alcohol at the age of ten and taking drugs at the age of twelve. He stole cars and committed robberies, even two in one day.

But Bostic changed in prison: He graduated from school, founded a literature club, wrote 15 books himself - including his mother's biography - and above all fought for a change in the law in the state of Missouri that minors could no longer be sentenced to such long prison terms .

"I didn't have much hope," Bostic recalled in an interview. In May 2021, thanks to numerous supporters, the governor actually signed the amendment to the law he was calling for. The regulation known as the "Bobby Bostic Law" suddenly made it possible for numerous prisoners who had experienced a similar fate to be released on parole - including himself: Bostic's case ended up before the parole board.

"But I didn't know what to expect," he recalled on the BBC. "The parole board isn't a free pass out of prison." Most importantly, he needed someone to represent him legally. Bostic asked the very person who had sentenced him to this long sentence: Judge Evelyn Baker.

"Bobby was a 16-year-old kid who I treated like a full adult, which was wrong," said Baker, who was appointed Missouri's first black judge in 1983. She had become closer to Bostic's family over the years. "I've seen him transform from a juvenile delinquent into a very thoughtful, caring adult. He's grown up.” Even a victim of one of his robberies, with whom he corresponded through letters, supported Bostic's release — successfully.

On a sunny November morning in 2022, the time had finally come: Bostic was released. "If I could have cartwheeled, I would have," said Judge Baker. "It was like Christmas, New Year, all the holidays rolled into one. I started to cry. Bobby was free.”

But Bostic felt the pitfalls of life in freedom immediately. Family and friends picked him up from prison in Jefferson City - and of course wanted to go celebrate. So they drove to a restaurant with the ex-prisoner. "I got in the car and vomited my entire meal. When you get out of prison, you haven't driven the freeway in 27 years. There is this thing called motion sickness.”

At his sister's house (his mother died of cancer a few years after his conviction and his younger brother died as a result of a gunshot wound) Bostic was to recover. However, around 400 people turned up in those days to congratulate him. "They were lined up around the block," he recalls. "When I turned around, I shook hands with that person, that cousin, that aunt, that uncle, that friend... I was up until two in the morning."

Today, the 44-year-old leads a modest life. He runs a charity with his sister that supports low-income St. Louis families. Bostic earns his living from the books he has written and lives in a one-room apartment. Sometimes he goes to a basketball game or plays with his little niece.

"I can hardly survive with what I'm doing now," says Bostic. He therefore hopes for a permanent position in social work. Especially since the time in prison has left its mark. For example, that he will probably remain on probation - with all the associated conditions - for the rest of his life. "I'm still wrestling with a few things. But other than that, life is beautiful out here, every day.”

For example, he looks in the fridge and sees the variety of things that are there. Or enjoy a bath in the bathtub that he has not been able to take for 27 years. Or about the birds chirping in front of his apartment. "I don't take anything for granted, nothing at all."

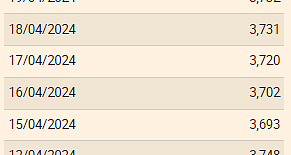

The Euribor today remains at 3.734%

The Euribor today remains at 3.734% Germany: the trial of an AfD leader, accused of chanting a Nazi slogan, resumes this Tuesday

Germany: the trial of an AfD leader, accused of chanting a Nazi slogan, resumes this Tuesday New York: at Columbia University, the anti-Semitic drift of pro-Palestinian demonstrations

New York: at Columbia University, the anti-Semitic drift of pro-Palestinian demonstrations What is Akila, the mission in which the Charles de Gaulle is participating under NATO command?

What is Akila, the mission in which the Charles de Gaulle is participating under NATO command? What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated)

What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated) Vaccination in France has progressed in 2023, rejoices Public Health France

Vaccination in France has progressed in 2023, rejoices Public Health France Food additives suspected of promoting cardiovascular diseases

Food additives suspected of promoting cardiovascular diseases “Even morphine doesn’t work”: Léane, 17, victim of the adverse effects of an antibiotic

“Even morphine doesn’t work”: Léane, 17, victim of the adverse effects of an antibiotic MEPs validate reform of EU budgetary rules

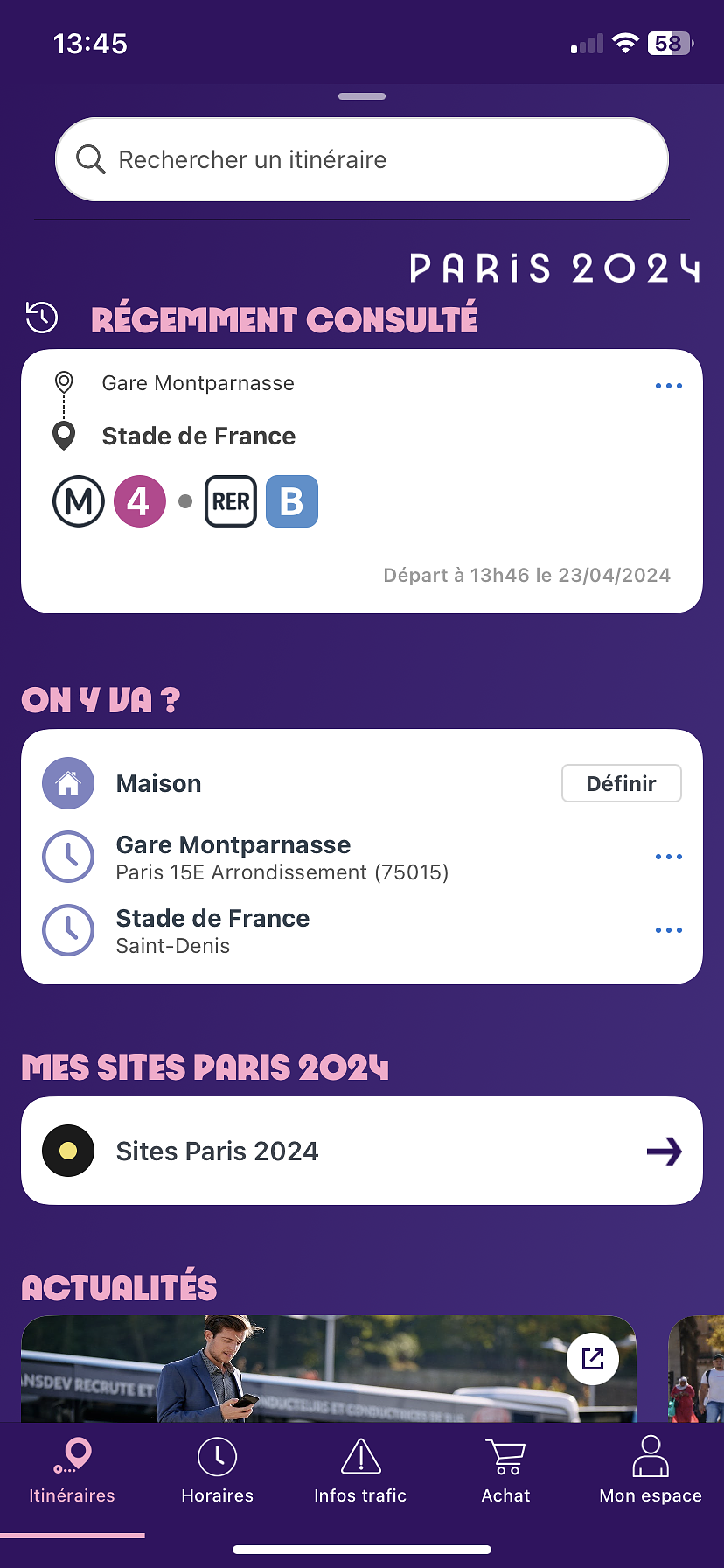

MEPs validate reform of EU budgetary rules “Public Transport Paris 2024”, the application for Olympic Games spectators, is available

“Public Transport Paris 2024”, the application for Olympic Games spectators, is available Spotify goes green in the first quarter and sees its number of paying subscribers increase

Spotify goes green in the first quarter and sees its number of paying subscribers increase Xavier Niel finalizes the sale of his shares in the Le Monde group to an independent fund

Xavier Niel finalizes the sale of his shares in the Le Monde group to an independent fund Owner of Blondie and Shakira catalogs in favor of $1.5 billion offer

Owner of Blondie and Shakira catalogs in favor of $1.5 billion offer Cher et Ozzy Osbourne rejoignent le Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

Cher et Ozzy Osbourne rejoignent le Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Three months before the Olympic Games, festivals and concert halls fear paying the price

Three months before the Olympic Games, festivals and concert halls fear paying the price With Brigitte Macron, Aya Nakamura sows new clues about her participation in the Olympics

With Brigitte Macron, Aya Nakamura sows new clues about her participation in the Olympics Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy

Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Serie A: Bologna surprises AS Rome in the race for the C1

Serie A: Bologna surprises AS Rome in the race for the C1 Serie A: Marcus Thuram king of Italy, end of the debate for the position of number 9 with the Blues?

Serie A: Marcus Thuram king of Italy, end of the debate for the position of number 9 with the Blues? Milan AC-Inter Milan: Thuram and Pavard impeccable, Hernandez helpless… The tops and flops of the derby

Milan AC-Inter Milan: Thuram and Pavard impeccable, Hernandez helpless… The tops and flops of the derby Ligue 2: Auxerre leader, Bordeaux in crisis, play-offs... 5 questions about an exciting end of the season

Ligue 2: Auxerre leader, Bordeaux in crisis, play-offs... 5 questions about an exciting end of the season