The Credit Suisse bailout is a broken promise. Exactly what happened to her was what should never happen again after the financial crisis of 2008: taxpayers took a risk with a struggling bank in order to avoid the supposedly greater risk of its liquidation. Regardless of whether such an approach prevents a possible global financial crisis, nobody should sugarcoat it. The cause should and must have consequences.

A few days ago, representatives of the European financial sector were looking smugly in the direction of California. The Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), which specializes in founders, unexpectedly collapsed there, raising the question of whether a similar scenario could be repeated elsewhere. The answer a few days ago was almost unanimously: no.

After all, it was said that the SVB not only pursued a very special business model. She was also less prepared for a possible imbalance. The authorities in the USA had relaxed some regulatory requirements. In Europe, on the other hand, the officials had remained steadfast. According to the widespread opinion, this would now pay off.

Are you kidding me? Are you serious when you say that. Just a week later, the picture has changed dramatically. With Credit Suisse, one of the most important banks in the world, has taken refuge in a state-orchestrated forced merger with its eternal rival UBS. The rescuer has her involuntary assignment duly secured.

The SNB provides liquidity totaling CHF 200 billion. And the government in Geneva guarantees nine billion francs for possible losses. How high the hurdles are is secondary. The important thing is that it is once again taxpayer money.

And that's exactly what should never happen again - actually. For more than a decade, regulators around the world have been making enormous efforts to do this. In a complex process, they identify the riskiest banks in the world every year. Credit Suisse was last ranked 23rd out of 30. These risky banks have to meet stricter requirements than others to ensure that there is no doubt about their stability. In addition, banks around the world have drawn up so-called "wills" that describe in detail for each national company how they are to be handled carefully in the event of a crisis.

There are also so-called bail-in bonds, which are converted into equity in the event of a crisis and are intended to provide an additional loss buffer. None of this could prevent the Swiss bank from rapidly losing trust - none of it was used.

Instead, Switzerland of all places has summarily suspended elementary rights such as the control of competition and the participation of shareholders in a takeover. It is hard to foresee what consequences this will have for a location that benefits like no other from the promise of neutrality and legal certainty.

However, the questions arising from the debacle extend far beyond Switzerland. When the acute storm has passed, the right lessons must be learned. Simply making even more and even more detailed specifications for banks is not necessarily the right solution. The level of regulation is already unmanageable and not suitable for reassuring unsettled investors.

In addition, it is questionable whether Credit Suisse would have remained stable if it had had a few percentage points more equity or a few billion more liquidity. She met all of the applicable formal requirements right up to the end. She was hunted down by the fear of her customers and business partners.

Nor can the answer be that politicians and supervisors become more involved in the specific business policies of banks. In the crisis 15 years ago, the German Landesbanken impressively showed what fatal consequences this commitment can have.

The correct answers are much easier. They start, as so often, with control and culture within a company. Good corporate governance has been discussed for 20 years now. Since then, the formal requirements for the independence and qualifications of supervisory board members have increased steadily. Nevertheless, the proximity of the supervisory body to the operational management of the company is often far too great. Credit Suisse is an impressive example of where this can lead.

The takeover of Credit Suisse by the major bank UBS in Switzerland has evidently failed to inspire confidence in the banks among investors in Europe. Bank shares in Germany and France plummeted.

Source: WORLD

Under the largely inexperienced and conflict-averse lawyer Urs Rohner, who previously worked in Germany as head of the television group ProSiebenSat.1. tried, a culture of ruthless profit maximization was able to establish itself. The result was more and more scandals.

And that for many years. The supervisors in Switzerland did not therefore remain idle. Little did they realize the existential threat these scandals posed to the bank. Because they battered their most important capital, which cannot be recorded with any checklist, no matter how sophisticated: the trust of their customers.

How cracked that was, had long been obvious. Last year, investors and companies not only withdrew securities worth well over CHF 100 billion from their custody accounts, they also withdrew a significantly larger sum from accounts.

The right reaction can therefore only be an earlier, more consistent intervention. The inspectors must not lose themselves in the thicket of regulations, but must focus more on the specific circumstances. A scandal is almost never an isolated case, but almost always a symptom that something is fundamentally wrong. In future, supervisors will have to pay at least as much attention to this as to their formal requirements.

In addition, it simply takes more courage. In the current situation, testing the carefully worked out processing rules at Credit Suisse of all places would probably have been an experiment with too high a stake. In other cases - such as the German state banks HSH Nordbank and NordLB - it would have been possible. Nevertheless, those involved balked and took refuge in compromises that were agreed upon at the last minute.

The German financial regulator BaFin must also learn the lessons. Their boss Mark Branson can at least look back on hopefully helpful experiences. Before moving to Germany in the summer of 2021, he headed an authority that was considered internationally exemplary at the time: Finma in Switzerland, which is responsible for Credit Suisse.

"Everything on shares" is the daily stock exchange shot from the WELT business editorial team. Every morning from 7 a.m. with our financial journalists. For stock market experts and beginners. Subscribe to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcast, Amazon Music and Deezer. Or directly via RSS feed.

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction

His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial?

Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial? What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain?

What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain? Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50

Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50 H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States

H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation

Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application

Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application “I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing

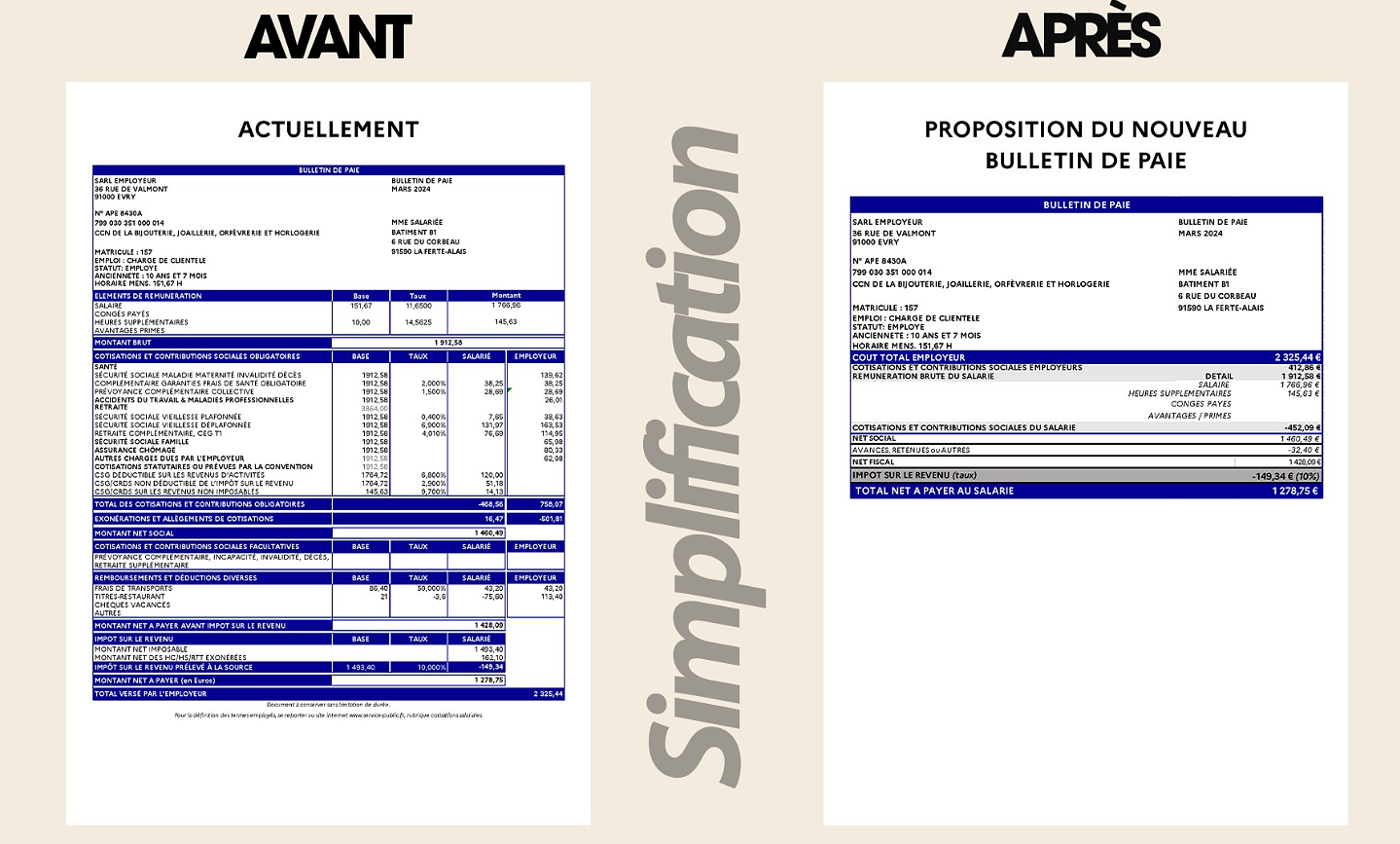

“I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing “I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy

“I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy 25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits

25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan

At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga

Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker

Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League

Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops

OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet

Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid

Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid